Down but not out! This is the theme of Resilient, a new award-winning short film that recorded Tommy Watson’s inspiring journey from a homeless senior in high school to a top football player in America and a strong leader in education. Despite being in foster homes, living in nearly 30 different locations growing up, being homeless and without any parental supervision, protection or support, Watson beat the odds, and earned four college degrees, including a doctorate in education leadership.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and the transition to remote and hybrid learning, homeless students faced tremendous challenges as they strove to learn and achieve in school. “As a nation, we must do everything we can to ensure that all students — including students experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity — are able to access an excellent education that opens doors to opportunity and thriving lives,” U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said in a release. To support homeless students to achieve academic excellence, school leaders need funding, resources, and strategies.

As the number of homeless students grows every year across many public schools in the U.S., policymakers should increase awareness of how to better serve them. To help school leaders to better serve this disadvantaged student population, the Center for Public Education (CPE) of the National School Boards Association (NSBA) gathered information from federal agencies, state governments, and academic studies, and conducted research on the following questions:

- Who are homeless students? (Definition of homeless students)

- How many homeless students attend public schools?

- Where do homeless students live and go to school?

- What are some characteristics of homeless students?

- How do homeless students perform academically?

- What are some funding sources to support homeless students?

Who Are Homeless Students?

Homeless students are defined as students who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, that is, students living in shared housing, hotels or motels, shelters, and unsheltered places (such as cars, parks, abandoned buildings), according to the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. As a primary piece of federal legislation related to the education of children and youth experiencing homelessness, the Act authorizes the federal Education for Homeless Children and Youth (EHCY) Program. In 2015, the Act was reauthorized by Title IX, Part A, of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

How Many Homeless Students Are Enrolled in Public Schools?

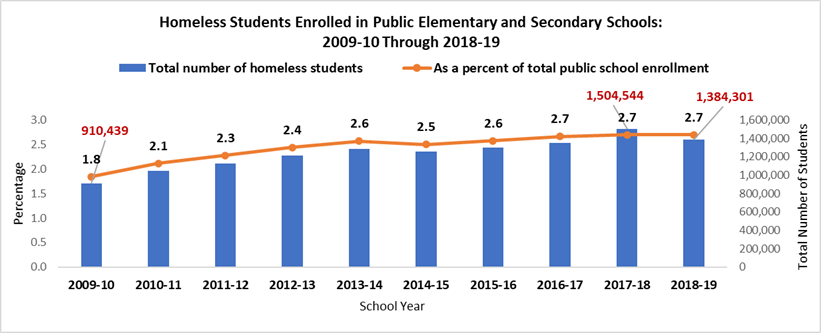

Since 2008, the number of homeless students identified by public schools each year has increased by more than 100%, from approximately 680,000 to 1,384,000 students in 2019 (Figure 1). In the 2016-17 school year, the number of homeless students exceeded 100,000 in California (262,935), New York (148,418), and Texas (111,177). At the same time, there were more than 50,000 homeless students In Florida (75,106) and Illinois (51,617).

Figure 1. Number and Percentage of Homeless Students in Public Schools

Source: Homeless students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by grade, primary nighttime residence, and selected student characteristics: 2009-10 through 2016-17; National Center for Homeless Education (NCHE) (seiservices.com)

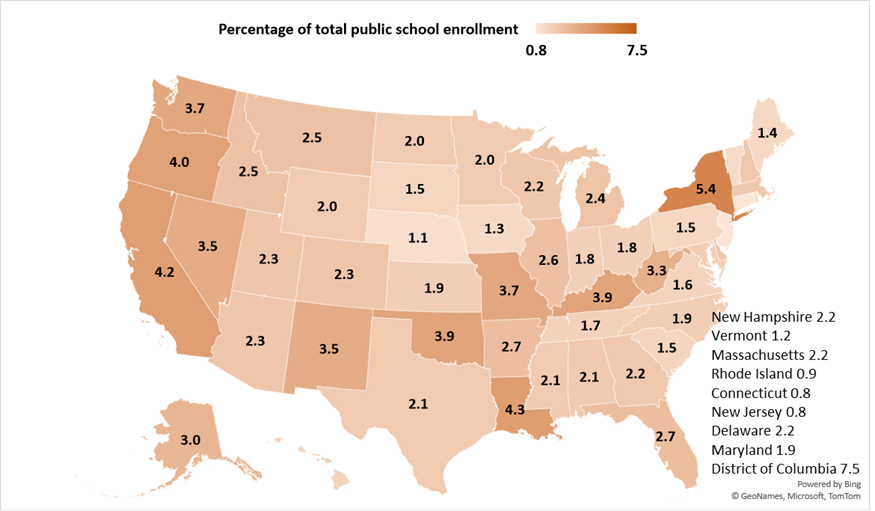

In Washington, D.C., and 12 states (New York, Louisiana, California, Oregon, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Washington, Missouri, Nevada, New Mexico, West Virginia, and Alaska), the percentages of homeless students enrolled in public schools were higher than the national average. As shown in Figure 2, the proportion of homeless students in Washington, D.C., reached 7.5% of its public schools’ population. By contrast, in Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut, the percentage of homeless students was less than 1%.

Figure 2. Percentage of Homeless Students Enrolled in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools, by State or Jurisdiction: 2016-17

Source: Number and percentage of homeless students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by primary nighttime residence, selected student characteristics, and state or jurisdiction: 2016-17

Among the 120 largest school districts in the U.S., New York City enrolled approximately 129,000 homeless students during the 2016-17 school year, and became the school district with the most homeless students. In the same school year, three school districts ― Los Angeles Unified (Calif.), City of Chicago (SD 299) (Ill.), and Clark County (Nev.) ― enrolled more than 10,000 homeless students, respectively. Percentagewise, in four public school districts (New York City, Santa Ana Unified and San Bernardino City Unified in California, and Mobile County in Alabama), more than 10% of the public school students were homeless.

Where Do Homeless Students Live and Go to School?

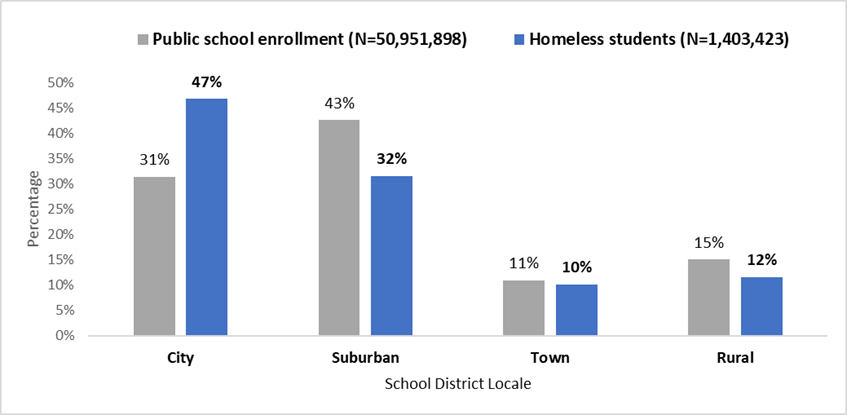

Geographically, three out of four homeless students live in cities (47%) and suburban areas (32%) (Figure 3). In the 2018-19 school year, approximately 77% of homeless students lived in doubled-up or shared housing (i.e., temporarily sharing the housing of other persons due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or other reasons such as domestic violence); 12% lived in shelters, transitional housing, or awaiting foster care; 7% lived in hotels or motels, and 4% unsheltered (e.g., living in cars, parks, campgrounds, temporary trailers ― including Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) trailers ― or abandoned buildings).

Figure 3. Percentage of Public School Enrollment and Percentage of Homeless Students Enrolled in Public Schools, by School District Locale: 2016-17

Source: Number and percentage of homeless students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by school district locale, primary nighttime residence, and selected student characteristics: 2016-17

In 11 states, more than 80% of homeless students lived in shared housing. In Mississippi, 92% of the state’s 10,000 homeless students lived in shared housing because of economic hardship, domestic violence, or other reasons during the 2016-17 school year. The same situation was reported in other states:

- Arkansas (88% of the state’s 13,104 homeless students lived in shared housing).

- Oklahoma (87% of the state’s 27,096 homeless students lived in shared housing).

- Alabama (86% of the state’s 15,931 homeless students lived in shared housing).

- Utah (86% of the state’s 15,438 homeless student lived in shared housing).

While in many states, about 70% of homeless students live in shared housing, this is not the pattern in Massachusetts, Washington, D.C., New York, Pennsylvania, Wyoming, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Arizona. In Massachusetts, among the 20,872 homeless students, 45% lived in shelters, transitional housing, or were awaiting foster care placement during the 2016-17 school year.

Nationwide, only about 7% of homeless students live in hotels or motels, but 16 states reported rates higher than 10%. In Vermont, 20% of its 1,097 homeless students, and in Georgia, 18% of its 38,336 homeless students lived in hotels or motels in the 2016-17 school year.

Across the country, only about 4% of homeless students are unsheltered. However, in Kentucky, 12% of its 26,826 homeless students, and in Oregon, 10% of its 24,322 homeless students were reported living in cars, parks, campgrounds, abandoned buildings, and other unsheltered places during the 2016-17 school year.

Among the 120 largest school districts in the U.S., nine reported that over 90% of homeless students lived in shared housing in the 2016-17 school year. These districts were Milwaukee (Wis.), Jefferson Parish (La.), Jordan (Utah), Santa Ana Unified (Calif.), Loudoun County (Va.), San Bernardino City Unified (Calif.), Mobile County (Ala.), Long Beach Unified (Calif.), and Baltimore City (Md.).

During the 2016-17 school year:

- In six large school districts, more than one third of homeless students reported living in hotels or motels. The districts were Gwinnett County (Ga.), Lewisville ISD (Texas), Virginia Beach City (Va.), DeKalb County (Ga.), Cobb County (Ga.), and Cumberland County (N.C.).

- In Boston (Mass.), 83% of homeless students reported living in shelters, transitional housing, or awaiting foster care placement. In Philadelphia City (Pa.) and Omaha (Neb.), more than 40% of homeless students reported such living conditions.

- In Texas, two school districts ― United ISD and San Antonio ISD ― reported that more than 30% of their homeless students were unsheltered.

What Are Some Characteristics of Homeless Students?

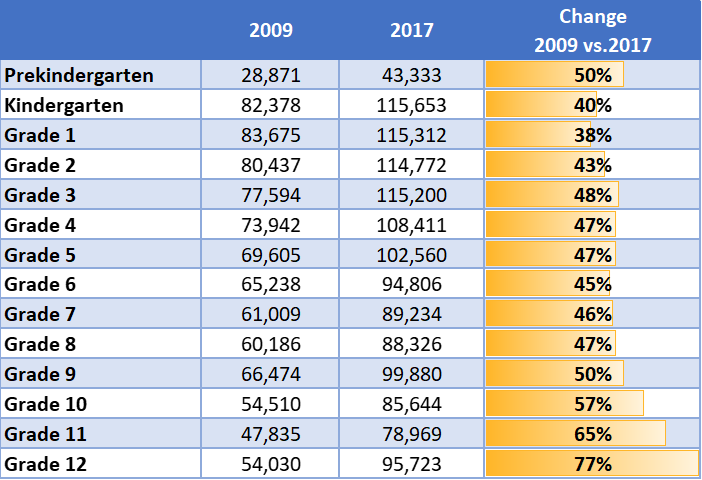

The number of homeless students has been growing every year in every grade level (Table 1). Between 2009 and 2017, the number of homeless students enrolled in public high schools increased by approximately 104,000; the number of homeless 12th-graders increased by 77%. During the same period, approximately 219,000 more young homeless students enrolled in pre-K to grade 5; prekindergarten experienced 50% increase in enrollment of homeless children.

Table 1. Homeless Students Enrolled in Public K-12, by Grade: 2009 vs. 2017

Source: Homeless students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools, by grade, primary nighttime residence, and selected student characteristics: 2009-10 through 2016-17

Homelessness is a dramatic disadvantage for students, both physically and psychologically, but some homeless students experience additional hardships and challenges. In the 2016-17 school year:

- Approximately 18% of homeless students were students with disabilities.

- About 16% of homeless students were English language learners.

- Nearly 9% of homeless students were unaccompanied homeless youth or youth who were not in the physical custody of a parent or guardian. This category includes youth living on their own and youth living with a caregiver who was not their legal guardian.

- More than 1% of homeless students were migrant students, who were either migratory workers or the children of migratory workers who moved to obtain temporary or seasonal employment in agriculture or fishing.

During the same school year, nearly half of the homeless students with disabilities were in five states ― California (15%), New York (14%), Florida (6%), Texas (5%), and Illinois (4%); about two-thirds of homeless students who were English language learners participated in K-12 public education in three states – California (39%), New York (15%), and Texas (9%).

- Among the migrant homeless students, 34% went to school in California, 11% in Washington, 7% in Oregon, and 7% in Texas.

- At district level, approximately 10,000 unaccompanied homeless students attended schools in three districts ― New York City (6,380), City of Chicago (SD 299) (2,070), and Fairfax County in Virginia (1,087).

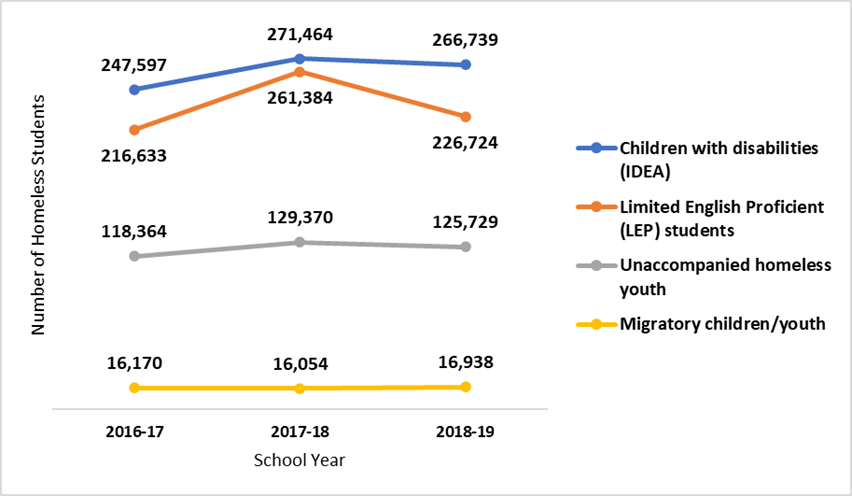

Between 2017 and 2019, the number of homeless students with disabilities increased by nearly 20,000; the number of homeless students who were English language learners increased by more than 10,000 (Figure 4). At the same time, the number of homeless students who were unaccompanied youth went up 6%, and migrant homeless students increased 5%.

Figure 4. Number of Homeless Students, by Student Characteristics: 2016-17 Through 2018-19

Source: National Center for Homeless Education (NCHE) (seiservices.com)

How Do Homeless Students Perform Academically?

Some research shows that only 64% of homeless students graduate from high school, compared to a national average of 78% for low-income students and 84% for all students. According to one report, students experiencing homelessness are 87% more likely to drop out of school than their stably housed peers. Other research states that without a high school diploma, youth are 4.5 times more likely to experience homelessness later in life.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) could not generate a national graduation rate of homeless students because not all states reported the public high school 4-year adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR) of homeless students. However, in general, the high school graduation rate of homeless students is much lower than that of their peers who are not homeless. Among the states that reported the statistics, in the 2018-19 school year:

- In Kentucky, the graduation rate of homeless students was only 16%, while the state graduation rate was 91%.

- In Minnesota and Washington, D.C., the 4-year ACGR was 49%. In other words, fewer than half of homeless students graduated from high school.

- In 27 states, the 4-year ACGR was between 52-67%; at least one in three homeless students could not graduate from high school.

Evidence shows that homelessness is a serious negative factor that affects student achievement. According to a 2019 report about the homeless students in New York City, fewer than one in four (23%) met grade-level standards in English language art (ELA) in the 2016-17 school year, which was almost half the rate of housed students who scored proficient on the ELA assessment (43%). On the statewide math assessment, homeless students also scored proficient at half the rate of their housed classmates (20% vs. 40%).

In the same report, researchers suggested that among homeless students, those living in doubled-up housing were more likely to meet grade-level proficiency standards on their ELA assessment (26%), while those living in shelters were less likely to obtain a proficient score (17%). This trend was also found in the math assessment, in which 24% of homeless doubled-up students scored proficient compared to only 12% of students in shelters.

Chronic absenteeism is often reported as a factor in the low academic achievement of homeless students. Researchers from the University of Southern California examined how homelessness affects students’ mathematics and attendance outcomes within the Los Angeles Unified School District. They found that students who experienced homelessness between fourth and eighth grade scored 0.13 standard deviations lower on math tests and missed additional 5.8 days of school than their peers who never experienced homelessness. “The average eighth-grader in the sample misses 7 days of school, thus homelessness adds almost six additional days absent in a 180-day school year (an 80% increase)” (Gregorio et al., 2020).

What Are Some Funding Sources to Support Homeless Students?

“All students experiencing homelessness are eligible for Title I services even if they are not enrolled in Title I schools,” according to the U.S. Department of Education (ED). Recently, ED is encouraging states to complete their applications for “Round 2 of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021’s Homeless Children and Youth Fund (ARP-HCY), which will deliver a collective $600 million in additional support to students in dire need this summer and before the start of the school year.”

According to ED, all public school districts must comply with the requirements of the McKinney-Vento Act to identify and serve school-age children and youth experiencing homelessness. Specifically, every state educational agency (SEA) must have an Office of the Coordinator of Education for Homeless Children and Youth, and the SEA must competitively award 75% of its annual allocation for homeless students to local educational agencies at least once every three years.

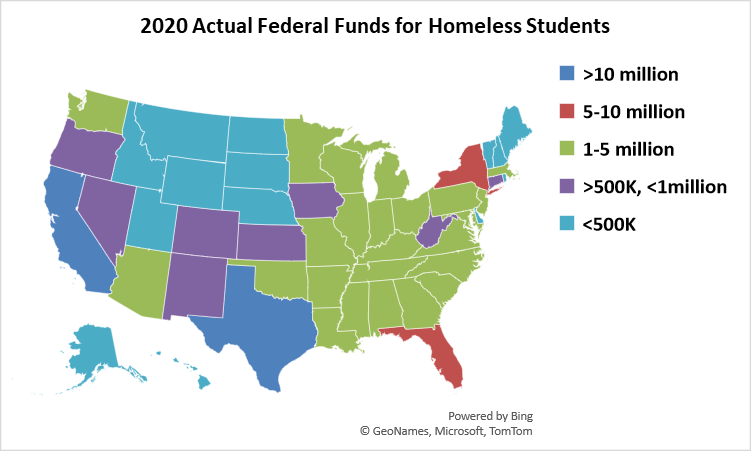

In 2020, two states – California and Texas – received more than $10 million for educating homeless students (Figure 5). Two states – New York and Florida – received $5-10 million for the education of homeless students. Nearly half of the country (24 states) received $1-5 million for the education of homeless students; most of the states are in the east coast, the Midwest, and the South. States in the West and the Northeast were more likely to receive less money for this category. This pattern is consistent with the density of homeless student population.

Figure 5. Grants from the U.S. Department of Education for Homeless Children and Youth Education, by State: 2020

Source: Fiscal Year 2019-FY 2021 President's Budget State Tables for the U.S. Department of Education

Conclusions

Homelessness has been steadily rising in major cities across the United States. Children under 18 comprise nearly a quarter of the homeless population (Henry et al., 2017). Researchers predict that the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely result in more families facing homelessness, and consequently, large urban school districts across the country face the challenge of identifying and serving an increasing number of homeless students.

During the pandemic, many school districts struggled to serve homeless students. For example:

- In New York City, the department of education announced that it would pay for summer school taxis for homeless students and those with disabilities after facing criticism from advocates.

- In Indiana, an Indianapolis tutoring program ― School on Wheels ― tried to meet homeless students where they were, but the capacity of this program was limited. According to the Indiana Department of Education, approximately 16,380 Indiana students were experiencing homelessness, and the need for tutoring homeless students has been growing since 2018-19.

- In Philadelphia, schools experienced a shortage of resources to serve homeless students because school leaders did not have accurate data about homeless students. Research shows that the number of Philadelphia high school students who are homeless may be four times higher than what has been reported.

In summary, providing homeless students with equal learning opportunities is not easy. According to ED, students experiencing homelessness have the right to enroll in school, even if they are missing paperwork that is normally required for enrollment, such as a birth certificate, proof of residence, previous school records, or immunization or other medical records. Homeless students have the right to enroll in their local school or stay in their school of origin, whichever is in their best interest. If attending their school of origin, they have the right to receive transportation to and from the school of origin.

Another big challenge is how schools can ensure that homeless students have equal access to online learning. According to NSBA, “Widespread home-based learning has highlighted a long-documented and persistent inequity of students that lack adequate broadband access.” This digital divide, commonly known as the homework gap, impacts approximately 1.4 million students who live in shared housing, hotels, shelters, or even in unsheltered places.

Growing up in foster homes, crisis centers, motel rooms, living with family and friends and bouncing around from place to place, Tommy Watson said, “I had no control over my life, so I came to school and tried to control that.” Down but not out — homeless students like Watson are resilient, hoping that education can change their lives. This hope should inspire school leaders and educators to make every effort to serve all homeless students.

Share this content