Innovative Practices that Support Student Learning During the Pandemic and Beyond

Overview

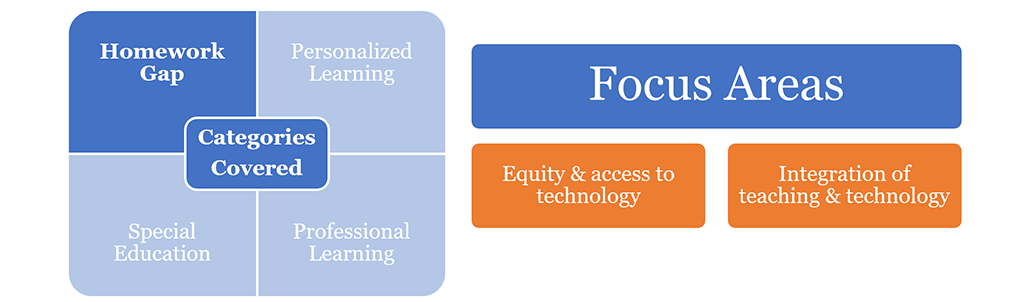

As part of NSBA’s “Public School Transformation Now!” campaign, the Center for Public Education (CPE) has prepared snapshots of innovative practices in place in school districts across our nation. NSBA defines public school transformation as a K-12 system rooted in access, equity, and innovation that equips each student with a more personalized learning experience focused on mastering 21st-century skills needed to succeed in a rapidly-evolving world. The snapshots are centered around four categories – personalized learning, professional learning, special education, and the homework gap. We profile three districts that demonstrate innovation in at least one of the four categories, using publicly available data to form our snapshots.

The goal of profiling these districts is to highlight real-life examples of transformation in our public schools. School transformation does not mean completely reinventing the wheel. Across the country, some districts have already worked around budget constraints and outdated state laws to provide truly innovative learning opportunities for students. What needs to happen next is scaling these practices and making changes to laws/policies that allow for full transformation to occur.

The work our educators and school leaders do every day should be appreciated, as they have worked tirelessly to provide quality learning experiences despite a myriad of challenges. During the pandemic, educators have stepped up to the challenge of rethinking lessons and instructional delivery models, hand-delivered meals, devices, and learning packets to students’ homes, and so much more. The snapshots we collected here are a celebration of the innovation that already exists in public schools.

We hope that by sharing these snapshots, school leaders can recognize today’s innovation in public education. To help school leaders gain more insight into education innovation, NSBA will begin releasing a series of case studies in the late Spring based on original research, namely in-depth interviews with school board members, superintendents, and teachers. The goal of this study is to provide examples of scalable practices that other school districts can consider adopting based on the needs of their own communities.

Snapshot #1: Sanborn Regional School District

|

Newton, New Hampshire |

|

~1,500 students |  |

89% of households with internet access |

How a Shift to a Competency-Based Learning Model Can Transform Teaching & Learning

Sanborn Regional School District (SRSD) is a small district in southern New Hampshire that has been recognized as one of the “25 Districts Worth Visiting” by Tom Vander Ark, founder and CEO of “Getting Smart,” for their successful K-12 implementation of a competency-based learning model. The district serves approximately 1,665 students across four schools. Class sizes are small, with a student/teacher ratio of about 11:1. The Sanborn community, which comprises the cities of Newton and Kingston, is suburban and 97% white.

For the 20-21 school year, SRSD developed a comprehensive re-entry plan to determine when in-person versus remote instruction would be safe for students. They began the school year with remote learning in September 2020 and have shifted between in-person and remote learning since then. The district has partnered with local YMCAs to provide childcare options to families when remote learning is in place.

The Sanborn Approach to Competency-Based Education

In 2005, New Hampshire became the first state to replace the Carnegie unit with a “mastery-based learning system of required competencies.” The Carnegie unit has been used for centuries to award academic credit based on a minimum number of instructional minutes. By shifting to a mastery-based system, the New Hampshire State Board of Education demonstrated its focus on proficiency for student advancement.

Brian Stack, principal of Sanborn Regional High School, embraced the shift and described his view on a competency-based model as follows: “I think of competency education as student-centered learning; it's a philosophical shift where we're really as educators trying to be laser focused on what kids know and are able to do -- and finding an assessment system that matches that so that we really feel good about the product that kids are walking away with.”

Personalized Learning at Sanborn High School

To ensure students consistently receive instruction that is relevant to their learning needs and achievement levels, the bell schedule runs on a flexible, six-day cycle with a corresponding letter for each day (A-F). Students meet with their adviser for traditional advisory activities on A and D days, while they engage in focused learning activities on the other days.

- Focused learning periods are 40 minutes long, with students either engaging in intervention (small group support), extensions (continuation of whole group lessons), or enrichments (activities beyond the curriculum).

- Students work one-on-one with their adviser to set the activities for the remainder of the cycle on A days.

- For example, a student may be asked to spend C day on an extended project with their music teacher and E day on reading intervention with their English teacher.

- The school utilizes scheduling software that allows advisers to easily set the schedule for the cycle and gives students the ability to see their schedule in a view-only capacity at any time.

Having a scheduling system that utilizes technology in place prior to the pandemic has paid dividends, as Sanborn High School has been able to continue using its scheduling software to provide students with focused learning time regardless of if classes are remote or in-person. The high school has also been able to continue its practice of regularly scheduled advisory meetings/check-ins that are not academically focused, which provides an outlet for students to build relationships with other students and staff. Creating systems that personalize learning regardless of whether students are in-person or remote has allowed Sanborn to truly differentiate for the needs of varied learners.

Grading in a Competency-Based Model

Sanborn uses formative and summative assessments to determine a student’s overall grade. Formative assessments are ongoing measures for learning that provide immediate feedback to teachers and students regarding student learning during a unit. Summative assessments, on the other hand, are measures of learning that are given at the end of a unit.

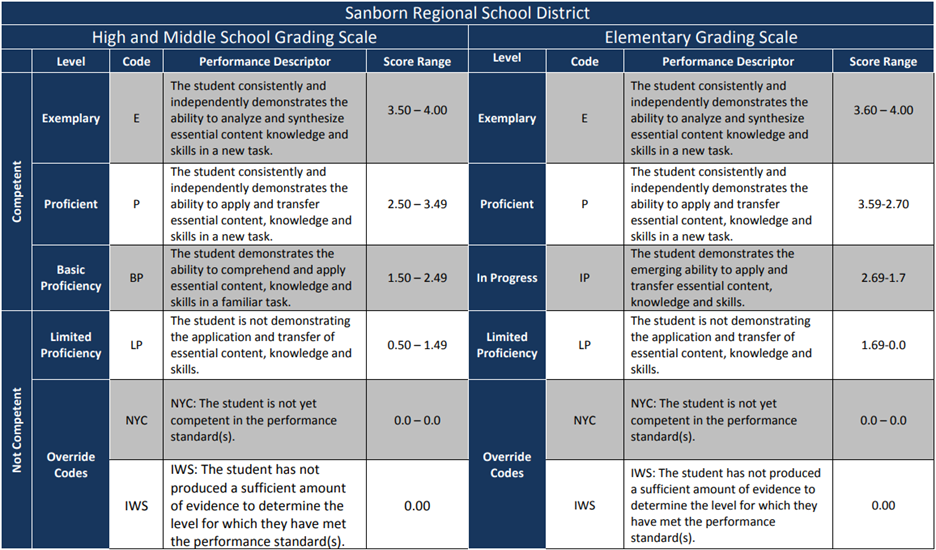

In the initial phase of implementation at Sanborn High School, Principal Brian Stack worked with faculty to ensure grades reflected what students learned rather than what students earned. A common set of grading practices were established and agreed upon:

- Academic performance is reported separately from work habits and behavior (e.g., participation, timeliness) in the grading system.

- Formative and summative assessments were separated, with the purpose of formative assessments being a way to provide feedback rather than serve as a major grading component.

- Summative assessments were developed by linking performing indicators to specific competencies in the grade book.

- Students are given the opportunity to take assessments multiple times, with an emphasis on truly mastering the subject matter.

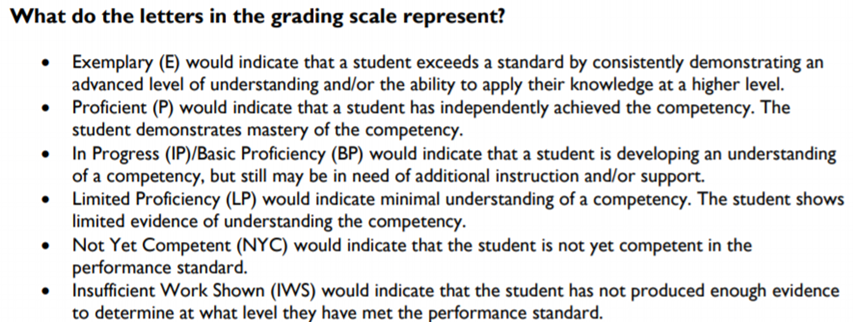

What resulted was a system of grading that looks very different from a traditional gradebook. SRSD’s K-12 grading scale is displayed in Figure 1. During the pandemic, Sanborn teachers have begun using a new online gradebook called Alma to report student academic progress. Both students and families/caregivers have online access.

Figure 1. Sanborn Regional School District’s Grading Scale

Source: Competency Based Instruction - Sanborn Regional School District (sau17.org)

Teacher Collaboration and Development

Principal Brian Stack outlined three major domains to support high school teachers with the shift to the new model in a blog for Aurora Institute: Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), Developing Expert Teachers, and Strategic Partnerships.

PLCs

PLCs foster collaborative learning among educators, with the purpose of planning and adjusting instruction to meet the academic needs of students. The PLC model, adopted at all SRSD schools, is structured so that teachers meet with other teachers who share the same students, rather than meeting with educators who teach the same subject.

PLC teams are given significant time to collaborate, with most teams meeting between two to three hours a week. Additional time for PLC collaboration was created by relieving teachers of duties like hall monitoring. They use this common time to plan and integrate their instruction, and create common performance assessments. The PLC model has led to a culture of accountability and support.

Developing Expert Teachers

In the early stages of implementing CBE, the high school developed a “training team” of teachers who took part in extensive district-funded professional development (PD) to build areas of expertise. The training team now supports teachers at their school site and across the district in multiple formats. They hold PD in the form of 1 on 1 support during planning periods, full workshop trainings during the summer, and online virtual support to their peers.

During the pandemic, the district has leveraged the capabilities of school counselors to work with staff to deliver a social-emotional curriculum that addresses a variety of needs and skills. The early investment to develop expert teachers allows the high school “to foster teacher expertise in-house” and drive continuous improvement.

Strategic Partnerships

Multiple partnerships aided SRSD with planning and implementation of a competency-based model. The high school worked with individual experts to develop formative and summative assessments tied to competencies and create more rigorous instruction. The district also partnered with multiple organizations to develop performance assessments, implement the PLC model, and more. Overall, SRSD worked with relevant partners to ensure successful implementation of the competency model.

What We Learned from SRSD

The greatest takeaway for why the school district has been successful with its shift to a competency-based model is a clear link between planning and implementation. The district started with a vision of a new learning model and worked in-house and with relevant external partners to make this a reality. The district fostered a culture of teacher collaboration through PLCs, invested in developing “expert” teachers, who in turn train fellow faculty in their respective domains, and worked with industry experts to create assessments mapped to competencies.

To realize the goal of personalizing the learning experience for students, “focused learning activities” - enrichments, intervention, or extensions – occur multiple times a week, with the activity based on the learning needs of the student. The district has been able to smoothly transition to the pandemic, utilizing the structures and practices put in place prior to the pandemic to provide quality learning opportunities. Overall, SRSD provides an excellent example for how to successfully transform schools through a model of education that places learning at the forefront.

Snapshot #2: Guilford County Schools

|

Guilford, North Carolina |

|

~72,000 students |  |

73% of households with internet access |

Sharing “Best Lessons” from Best Teachers “Asynchronously”

Not every student has the opportunity to sit in a classroom where a top teacher in the school district presents a great course. In Guilford County Schools (GCS), this opportunity has become accessible to all students this fall, thanks to the creative approach GCS took to face the crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

GCS is the third-largest district in North Carolina, serving nearly 72,000 students across 125 schools in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Almost half of the student population is non-White, including 34% Black and 8% Hispanic students. At least one in four families in the district lives in poverty, and about one in four students live in households without broadband internet.

GCS educators are committed to personalizing learning for each of their students, regardless of the circumstances in which they live. The district has 48 magnet and choice schools with 66 programs, from Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) to performing or visual arts, advanced academics, Spanish immersion, Montessori, health sciences, and aviation. To continue personalized learning during the pandemic, GCS overcame numerous challenges and provided technology support for students to continue their education.

- Since schools closed in mid-March of 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic, GCS has distributed nearly 18,000 laptops and tablets to students to support online learning.

- Since March 18, the beginning of online learning, 70,065 GCS students – about 96% of the district’s total enrollment – have logged into Canvas, the district’s learning management system.

- District data indicates that most students – more than 80% – are engaged in online learning activities on a regular basis.

“As of Jan. 5, 2021, 73.5 percent of elementary students had returned for in-person instruction. The remaining students are either enrolled in the Guilford eLearning Virtual Academy or receiving remote instruction through their schools.”

Mobile Learning Centers in Guilford County Schools

To close the homework gap, GCS has adopted strategies such as SMART Buses and Mobile Learning Centers to support the engagement of vulnerable student populations.

- SMART Buses are school buses that go into historically underserved communities and allow students to use the vehicles’ hotspot capabilities to access the internet for free. This strategy allows students to fully utilize the online learning options the district is currently providing.

- GCS opened learning centers in 13 schools for students who lack internet access. The learning centers are strategically located in neighborhoods and communities where Census data indicates that more than two-thirds of households lack broadband connectivity. Opening learning centers in these areas made it easier for students to walk or ride their bicycles to the schools, or for families to make other arrangements. The service is free.

- The learning centers function similarly to an internet café. While there are a limited number of desktop devices available at the learning centers, most students bring their own devices. Students use their Student ID numbers to login to Canvas. Center supervisors help students access and navigate Canvas and other GCS applications. The centers also provide breakfast and lunch to students. Students who attend Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) schools do not need to pay for meals.

GCS Provides Students Access to Great Teaching in Innovative Ways

Device distribution and providing internet connectivity is not enough to bridge the opportunity gap. GCS school leaders were determined to take advantage of digital technology and provide each student with a high-quality learning experience. During the summer break, GCS leaders had the best teachers in the district pre-record lessons to be shared by all students in the fall semester.

Today, all GCS students have the opportunity to take asynchronous classes with the best GCS teachers in the form of pre-recorded lessons. While synchronous learning refers to real-time instruction that can occur in-person or online, asynchronous learning does not require real-time interaction. Instead, students have the flexibility to view lessons and complete assignments before their due dates based on their own schedules.

As we know, students are more engaged in learning when teachers use creative and interesting ways to present the material. During an interview with CNN, former U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan recognized GCS Superintendent Sharon L. Contreras and GCS leaders, who made numerous efforts to create high-quality learning environments and meet the needs of all students.

What We Learned from GCS

The homework gap needs to be solved strategically. So far, many school leaders have taken action to help disadvantaged students access digital devices and high-speed internet. Yet, it is not enough to ensure that every student engages in learning activities enhanced by digital environments. The lesson we learned from GCS is to use the best teachers as resources, pre-record lessons during school breaks, and offer students an equal opportunity to watch asynchronously. With the support of digital technology, all students can share best practices from the best teachers.

Snapshot #3: Nampa School District

|

Nampa, Idaho |  |

~14,000 students |  |

79% of households with internet |

Leveraging Technology to Support Students with Speech Therapy Goals on Their IEPs

Is special education ready for cyberspace? This question was asked by educators about ten years ago. In 2014, Professor Barbara Ludlow from West Virginia University argued that the move to digital learning was always a matter of when, not if, and that special educators should be actively seeking how to provide specialized instruction. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the “when” was not a choice anymore, and schools had to solve the issue of how to serve students with disabilities in remote learning.

While many schools were anxious about the fact that occupational, physical and speech therapists often serve students in a physical setting and that there are not good substitutes for that over video chat, the Nampa School District (NSD) in Idaho found specific, clear, and actionable strategies. In NSD, about 12% of the student population are students with disabilities, and 63% are economically disadvantaged. With technology, NSD effectively provided more tailored individual support for students who had speech therapy goals in their Individual Education Programs (IEPs).

Teletherapy - Deliver Specific Instruction to Individual Students

In a brick and mortar school environment, specialists such as speech language pathologists (SLPs) are often limited to conduct therapy in small groups due to scheduling constraints. By contrast, in the virtual world, these therapists have numerous options to deliver specific instruction to individual students, as they don’t have to work around the brick and mortar schedule. This is what researchers concluded recently, and exactly what happened in NSD.

During the pandemic, the NSD leaders purchased a new type of software for SLPs to deliver the appropriate services. At the same time, the district followed The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) – a federal law that requires the creation of national standards to protect sensitive patient health information from being disclosed without the patient's consent or knowledge – and partnered with a local company to access a HIPAA-required platform so that speech language pathologists could deliver services via telehealth.

One SLP complemented direct teletherapy with recorded homework, through which students recorded audio samples of them practicing with a parent. As a result, these students received all their support in a one-to-one or two-to-one student-to-SLP ratio, rather than in groups. In another case, a SLP who used to see multiple children from one family separately in their respective grade-level groups prior to school closures was able to see all students at once, thanks to the teletherapy implemented during COVID-19. In doing so, she was able to identify new opportunities for interventions that she had not seen previously when working with the students separately.

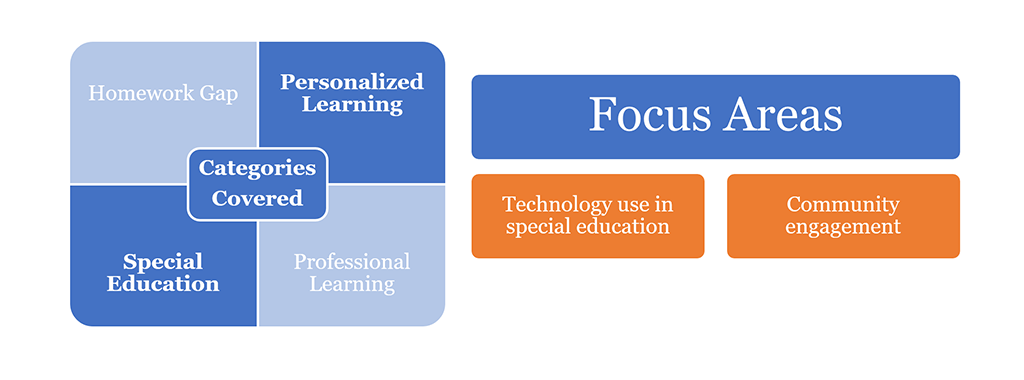

What We Learned from NSD

From telehealth to teletherapy, the Nampa School District creatively used “cyberspace in special education” to support students with speech therapy goals in their IEPs. Teletherapy may have a place in school transformation, as an example of leveraging technology and the flexible schedule to provide more tailored support in smaller groups. In the long run, personalized learning with the support of technology and community engagement should be a must.

Upon opening the NSD website, viewers can see immediately an icon – “Digital Resource tutorials for parents and students.” Both parents and students are provided with information about how to get assistance to use digital resources. Importantly, the NSD clearly describes its visions and goals of personalized learning in the digitally enhanced environments.

More significantly, developing a supportive community becomes a goal of personalized learning for every student, including students with disabilities. According to the NSD, a supportive community includes:

- Parents and families will be informed about personalized learning.

- Parents and families will support digital citizenship at home.

- Parents and families will support their students, teachers, and school through ongoing communication.

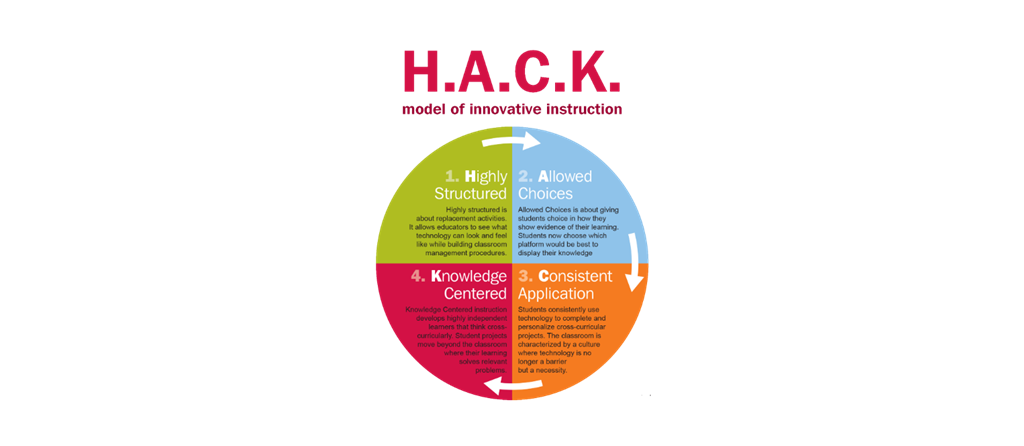

As framed in the NSD H.A.C.K. Model of Innovative Instruction (Figure 2), special educators can leverage technology to personalize learning for students with disabilities by:

- Establishing an instructional structure with both the assistance of certain type(s) of technology and the support from a learning community (e.g., students, parents, and teachers).

- Within the established instructional structure, providing choices about which platforms students feel appropriate for their learning and achieving their goals.

- Consistently using the instructional structure and technology chosen by the supportive learning community.

- Collecting relevant data from the learning platform and adopt competency-based learning and assessment to help students become independent, life-long learners.

Figure 2. The NSD H.A.C.K. Model of Innovative Instruction

Source: https://www.nsd131.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=1230959&type=d&pREC_ID=1443347

A recent study shows that one of the challenges that Nampa must address moving forward is how to support the highest-need students with disabilities, such as students who are medically fragile. In 2020, NSD staff were able to work with that type of student virtually to achieve basic outcomes, but district leadership believes there is more to do to ensure that they are meeting the needs of all students. While NSD does not have all the answers to effectively assist every student with disabilities in digital-based learning environments, the district leaders certainly understand the importance of building a supportive community for students with disabilities in personalized learning.

Prepared by NSBA Senior Research Analyst Jinghong Cai and Rishabh Chatterjee, LEE Policy Fellow in NSBA’s Federal Advocacy department on March 26, 2021