Katherine McDaniel, nurse practitioner supervisor and director of Nemours School-Based Health Centers, stands outside the Eisenberg health center, one of about 2,500 currently operating in 21 states in the U.S./PHOTO CREDIT: GLENN COOK

On a late summer morning, Jon Cooper is sitting on a desk in an empty second-grade classroom at Delaware’s Eisenberg Elementary School. The room’s rectangular footprint is one you see regularly on campuses built during the baby boom era of the late 1950s, a period of massive expansion for public schools.

“This is the exact same size as the room next door,” says Cooper, director of health and wellness for the Colonial School District, which serves more than 9,100 students in communities just south of Wilmington. “That’s remarkable, isn’t it?”

Remarkable, indeed, given that next door houses a full-service wellness center and clinic that has been in place since 2016, when Colonial became the first district in Delaware to open this type of facility in an elementary school. The clinic, staffed by the nonprofit Nemours Children’s Health, is credited with helping to turn around the high-poverty, majority-minority school thanks to fewer discipline and truancy referrals.

As schools nationwide grapple with student mental health challenges that were exposed and heightened during the pandemic, districts are looking at ways to provide systemwide services that go beyond what is taking place in the classroom. But there are obstacles—increased staffing shortages, ever-present financial challenges, and in some locales, political and cultural ones—that school leaders also must confront as they take on this task of innovation and transformation.

“Ask any superintendent the top issue they are facing, and they will tell you it’s student mental health,” says Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Oregon’s Beaverton Public Schools. “We know our kids are behind, but how do we accelerate learning when we know that they are struggling with their mental health? What is the balance we need to strike as school leaders?”

There are slivers of hope, including less stigma around mental health and signs that students are starting to rebound as they enter a third school year following the initial COVID-19 outbreak. In January, a national survey of school board members by Mental Health First Aid USA showed that youth mental health is their top concern by a significant margin, with calls for more evidence-based instruction and training for students. And in July, a nationwide Harris Poll showed parents and families are seeing gradual improvements in students’ mental and academic health.

“We know systems are inundated with quick fixes and shiny balls, and it’s tempting to reach for those things when you’re in a crisis,” says Rebecca Benghiat, president of The JED Foundation, which is working with AASA: The School Superintendents Association to create a comprehensive approach for districts to meet students’ mental health needs. “At the same time, the overall health and well-being of our students is complicated by a host of variables, so we have to think in complex ways to find solutions to these complex problems.”

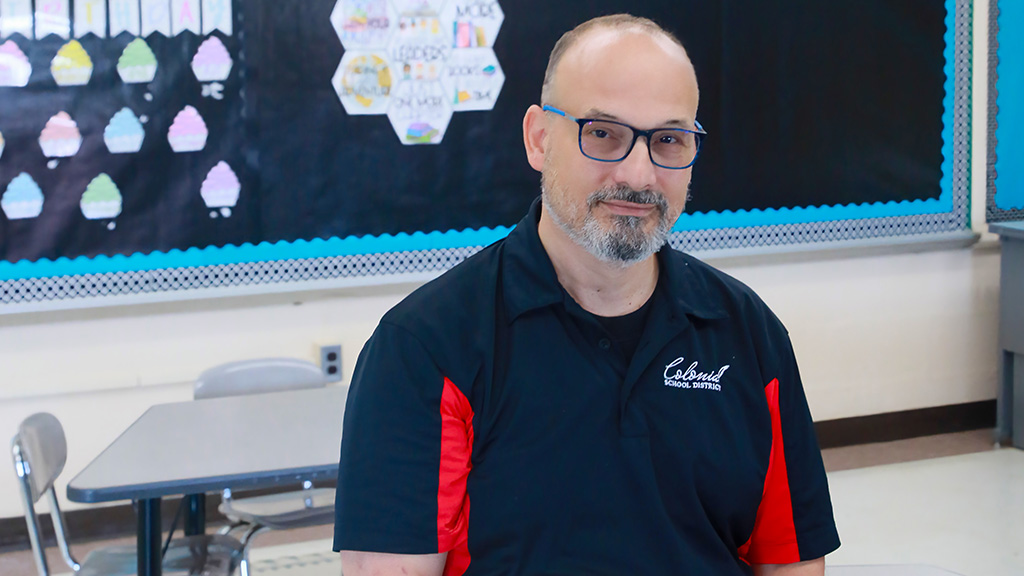

Jon Cooper, director of health and wellness for Delaware’s Colonial School District, sits in a second-grade classroom at Eisenberg Elementary. Next door, in a room the same size, is a full-service wellness center that has been credited with helping to turn around the high-poverty, majority-minority school./PHOTO CREDIT: GLENN COOK

One-stop shop

The issues are complex in Colonial, a densely populated district with eight elementary campuses, three middle schools, and a single comprehensive high school. All but one of the schools, most of which are within a five- to 10-minute drive of one other, are Title I campuses.

Colonial serves several small communities where the population is aging, meaning enrollment overall is declining because the district has fewer school-age children than it did in the past. Private and parochial schools, along with charters and a countywide vocational-technical campus also compete for students.

Delaware is the only state that mandates and funds school-based health centers in each of its traditional public high schools, but paying for sites at campuses in grades PK-8 falls to local jurisdictions. Several years ago, Colonial’s school board decided to fund a center at Eisenberg, a K-5 school nestled in a neighborhood surrounded by small houses that is close to the Delaware Memorial Bridge.

“One reason Eisenberg was picked was because of the service area,” Cooper says. “It’s very transient. Many of our families are Hispanic and have just come into the country. We have a large homeless population near the bridge and a number of families that are living in temporary housing in hotels.”

Eisenberg’s clinic, which includes an exam room, counseling office, laboratory, and small waiting area, is staffed with a pediatric nurse practitioner, medical assistant, psychologist, and social worker. All services are free and can be accessed without insurance or a visit to a doctor.

“It’s a one-stop shop,” Eisenberg Principal David Distler says of the center. “If we have a student with a mental health issue, we can get them help right away. If they don’t have their immunizations, we can make sure they get them. If a kid comes in sick, we can send them down the hall. It gives us a chance to be proactive and keep our kids in class where they need to be.”

Distler says the school had more than 1,200 discipline and truancy referrals in 2014, the year he became principal. Since the wellness center was put in place, those referrals steadily dropped prior to COVID, then increased in the days after students returned to school. By 2022-23, however, they had declined again to 130.

Colonial officials attribute the decline in referrals to the wraparound services provided at Eisenberg, including before and after-school care that allows students to be at school from 7:45 a.m. to 6 p.m. if necessary. Students also receive free breakfast and free lunch.

“Our school is definitely affected by environmental issues that are not related to the classroom, but have an impact on student learning,” Distler says. “Schools are designed to be hubs of the community, so if we can offer more services at the school, we’re going to make our community better. To me, this is the model every school should have.”

Can it be sustained?

With three plus decades in education, a dozen of those as a superintendent in three districts, Balderas feels like he has seen it all in just the past few years. Named National Superintendent of the Year in 2020, he left Eugene, Oregon, at the height of the pandemic to become superintendent in Edmonds, Washington. Then, two years later, he returned to Oregon after being named superintendent in Beaverton, a suburb of Portland that is home to the headquarters of Nike and Intel.

When Balderas arrived, Beaverton, which has 38,000 students and 54 schools, had been rocked by the fentanyl overdose deaths of several students in 2020 and 2021. The district now has fentanyl-specific lessons that are taught in health classes each year in grades 6-12.

“Kids became desperate to reengage during the pandemic, and we saw a number of them who started self-medicating as a way to deal with it,” says Balderas, who started his education career as a school counselor. “Mental health does not have a predictor sometimes; there are mental health issues in every one of our 54 campuses. Kids from different incomes and different backgrounds have all been impacted.”

Balderas, AASA’s president-elect, has spoken with superintendents across the country and says educators are all dealing with student mental health issues in their districts. “This is especially true in communities that are rural or high-impact urban, because the majority of those school districts don’t have the ability to provide what those in other wealthier communities do,” he says.

Using federal pandemic recovery funds, Beaverton has added social workers and behavioral health and wellness teams at several of its schools, but Balderas questions whether those programs can continue once the money runs out.

“We know it’s a best practice, but how can we continue to sustain it? It’s something we’re struggling with ourselves in my district, and we’re one of the fortunate ones,” he says. “We’re literally deep diving to see what we can reduce to keep these teams intact because we know they make a difference for kids.”

Balderas is optimistic about AASA’s partnership with The JED Foundation, which is working to develop a framework of best practices, support from experts, and data-driven guidance to support school districts in dealing with student mental health issues. Called “The District Comprehensive Approach,” the framework will expand a program the foundation created for high schools that focuses on suicide prevention and student mental health.

JED’s high school program focuses on seven themes: developing life skills, promoting social connectedness and a positive school climate, encouraging help-seeking behaviors, recognizing and responding to signs of distress and risk, ensuring access to effective treatment, establishing and following crisis management protocols, and promoting ways to keep dangerous items away from children.

“We recognize that district intervention sits at the district level, and there are levers to pull in school systems that only districts can pull, from funding decisions to policies and procedures to professional development,” Benghiat says. “Our hope is to help districts talk about the complex issues they are facing so they don’t go for the one solution or one tool that won’t produce the outcomes they’re expecting.”

A multipronged approach is being implemented this fall in North Carolina’s Durham Public Schools, which has made student and staff wellness a hallmark of its new strategic plan. The district has a new social-emotional learning curriculum that will be taught across all grades starting this fall. Instruction and workshops for students and families also are planned on ways to deal with the negative effects of community violence and how to seek help for student mental health issues. The district also has developed a data dashboard for its students that staff can use when writing intervention plans.

“These efforts are part of a comprehensive approach we will be taking to student wellness over the next few years,” says Laverne Mattocks-Perry, Durham’s senior executive director of student support services. “We know we can’t do this alone, and we are reaching out far and wide to get the help our students need. They deserve it.”

PROSTOCK-STUDIO/STOCK.ADOBE.COM

‘Come back strong’

The school-based health center at Eisenberg is one of about 2,500 operating currently in 21 states in the U.S., according to the School-Based Health Alliance. Despite long-standing research showing the effect the clinics have on student health and academic outcomes, the reason more are not available comes down to one word: funding.

Eisenberg is the only elementary school in Colonial with a full-service clinic, but Nemours has additional staff who float to the district’s other K-5 campuses. The services are paid for by a combination of district and county funds, reimbursements from Medicaid and private insurers, grants, and contributions from Nemours.

“This partnership is working because the school district and the health care system are committed to working through all of the bugs, and they are manifold,” Cooper says.

Katherine McDaniel, nurse practitioner supervisor and director of Nemours School-Based Health Centers, says her staff “really wants to fill in the gaps and augment what the schools already are doing well.”

“We don’t want to be the medical provider. We want to be part of the community and part of the school system,” McDaniel says. “Our approach is very collegial, and it’s tailored to the community we are working in. What we might do for Colonial might be very different from what we’re doing for another district because each community’s needs are different.”

Each week, Distler and his administrative team meet with clinic staff to review discipline and truancy referrals, determining whether students should meet with the school counselor, someone at the wellness center, or be referred to an outside service. New students and families are made aware of the services that are available on site and recommendations are made for primary care providers.

Nemours is currently helping Colonial expand its wellness center services to the district’s three middle schools. The district received a $200,000 grant from the county to open one center this fall, closing what both Distler and Cooper described as “an obvious gap” in services that needed to be addressed. Federal COVID-recovery funds will be used to pay for additional staffing for the next two years, but Colonial is seeking more grants and more help from the state to sustain the program.

When it comes down to showing what the health centers can do, Cooper and Distler point to Eisenberg’s post-pandemic success. Discipline and truancy referrals dropped 50% last year, and the school saw its test scores in English/language arts increase by 21% in fourth grade and 7% in fifth grade from 2021-22 to 2022-23.

“Our school has had a complete turnaround. It’s a totally different environment than it was, and we’re continuing to come back strong from the pandemic despite all the challenges it brought,” Distler says. “Students are in class. They’re not throwing fits. Teachers are able to teach, and families are able to get services when they need them. What more can you ask for?”

Glenn Cook (glenncook117@gmail.com), a contributing editor to American School Board Journal, is a freelance writer and photographer in Northern Virginia.

Share this content