When planning the special education department budget for Pennsylvania’s Upper St. Clair School District, Amy Pfender learned early to never count on the promised funding from the federally mandated Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

“You can’t really anticipate what the funding will be from year to year,” says Pfender, assistant to the superintendent of the suburban Pittsburgh district and, until recently, its director of student support services. “You have kind of an average that has come in,” she says, “but even that can fluctuate.”

Pfender remembers having to remove staff positions from proposed budgets because their salaries were dependent on IDEA funds. As it turned out, “that money was not coming in.”

Applause and frustration

That’s a refrain often associated with the historic legislation. Signed into law in November 1975, IDEA began dismantling the barriers to education for children with disabilities by requiring that public schools provide the access and support they need for a high-quality education.

As IDEA enters its 45th year, there is much to celebrate about the legislation. The Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) notes, for example, that “prior to IDEA’s passage, children with disabilities were shunned from school, and plagued by stereotypes, misconceptions, and low expectations. As a civil rights law… IDEA has revolutionized the lives of children with disabilities.”

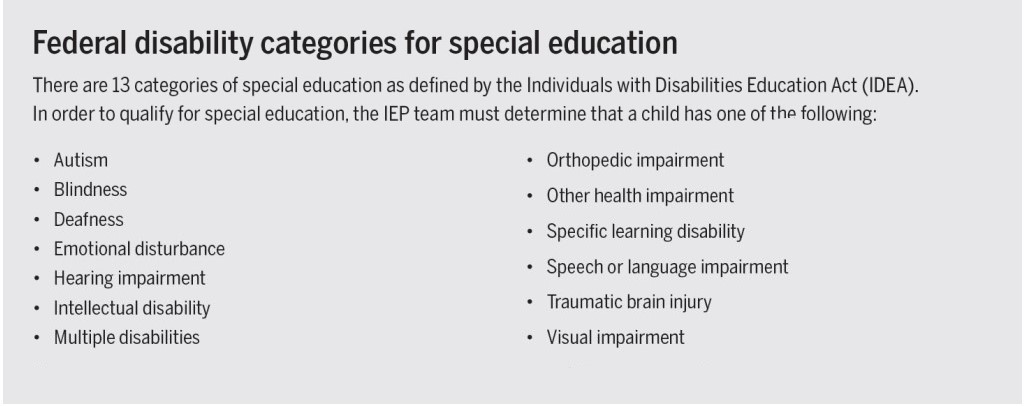

Approximately 7 million students, ages 3 to 21, with physical, cognitive, and learning disabilities —14 percent of all public school students—currently receive special education services under IDEA, according to the U.S. Department of Education. And two-thirds of those students are taught in general education classrooms alongside their nondisabled peers for 80 percent or more of their school day.

But mixed with the applause for the legislation is frustration that its full potential has yet to be realized because of long-standing underfunding. The federal government’s promised “full funding” contribution—40 percent of the excess costs of educating a student with disabilities—has consistently fallen far short. Federal funding dipped to roughly 15 percent in 2019, the lowest percentage level since 2001. That shortfall leaves already financially squeezed school districts to pick up an even larger share of the special education bill. Like most districts, Upper St. Clair turned to its general fund to pay for those essential but defunded special education staff positions. Officials at South Carolina’s Horry County Schools had to request a budget package of over $1 million from general revenue sources “in order to solely provide the additional personnel needed” for the 2019-20 school year, says Kristin Wilson, executive director of special education and federal programs for the district in the Myrtle Beach area.

“There are only so many dollars. There are only so many revenue resources,” Wilson says.

The need for such financial maneuvering exemplifies a key challenge faced by districts across the country when it comes to relying on the federal government’s commitment to help them meet their legal obligation to provide students with disabilities access to a free appropriate education in the least restrictive environment.

“I feel like the concept of funding and federal law are not talking to each other,” Pfender says. “It’s a constant challenge for districts to be fully responsive, but fiscally responsible.”

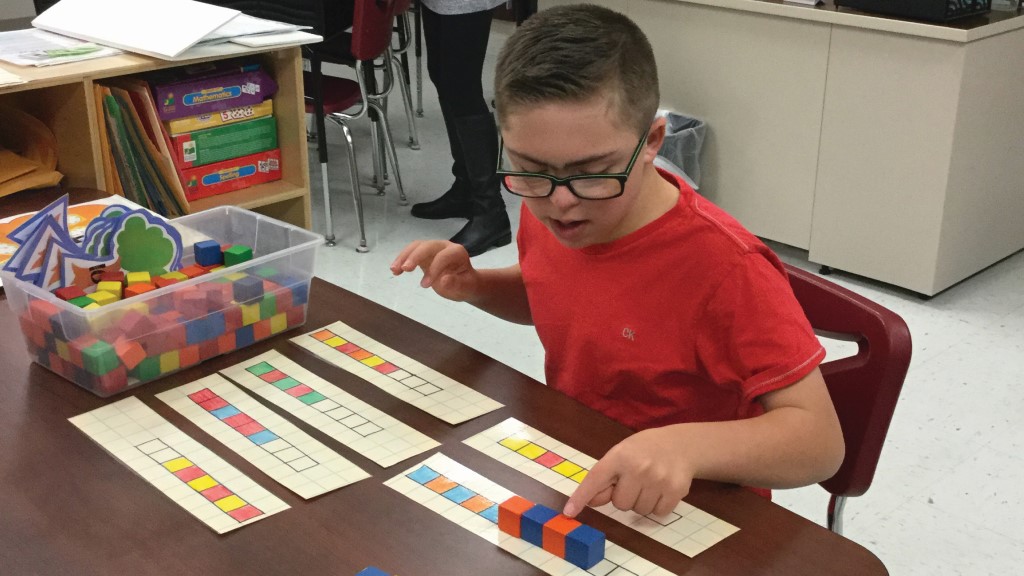

A Boyce Middle School student working on one-to-one math skills and continuing patterns in a resource classroom. Photo courtesy of Upper St. Clair School District.

By law, districts are obliged to provide the resources outlined in an Individualized Education Program (IEP)—the written document outlining services each public school child who is eligible for special education will receive—“regardless of their funding situations,” says Jenifer Harr-Robins, who researches special education finance issues at the American Institutes for Research (AIR). “Once those IEPs are developed, they have to be implemented.”

“If full funding for IDEA were provided by Congress, the possibilities to improve public education would be endless,” says Chip Slaven, NSBA’s chief advocacy officer. “Schools across the nation could increase resources for students with disabilities and expand opportunities to do other things that improve public education for all students, such as providing teachers with more robust professional learning, increasing access to high-speed broadband and adaptive technology important for personalized learning, and increasing other vital student supports.”

Funding push

A 2018 report by the National Council on Disability, an independent federal agency, said that: “Students with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of funding issues, which can include delays in evaluations or rejection of requests for independent educational evaluations, inappropriate changes in placement and/or services, and failures to properly implement individualized education programs (IEPs).”

Every year when Congress comes back and says that IDEA is going to be funded at the same level as the previous year, that means a cut to school districts. “We have more kids coming into the system, so there’s rising cost and more inflation in the budget,” says Kevin Rubenstein, director of student services for Illinois’ Lake Bluff School District 65 and policy and legislative chair for the Council of Administrators of Special Education.

The stalled IDEA Full Funding Act, introduced in Congress in March 2019 by Sens. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) and Pat Roberts (R-Kan.) and Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.), is a recent effort to increase IDEA Part B grants (the primary source of federal funding to states and districts for students with disabilities) over the next decade and fulfill the government’s full funding commitment.

Share this content