“…part of being an instructional leader is demonstrating your willingness and desire to learn alongside the teachers, or other leaders, that you are supporting. Whether you are literally sitting at the same table and rolling your sleeves, or you are engaged in a parallel learning experience that better equips you to support the learning of others, being a learner is an important part of being a leader. It allows you to model and support risk taking, builds empathy for the work of the teacher, and demonstrates your commitment to continuous improvement….”

—Melanie Ward, assistant superintendent, Pittsford Central School District, Pittsford, New York

“I just finished a classroom observation in Sara Ertel’s room. She was using highlighted feedback and goal setting to focus on student growth connected to mathematical concepts. This is not an observation of practices that I would have seen four years ago. Your work is impacting our work with students in ways I am just now starting to fully understand.”

—Marc Nelson, principal, Harris Hill School, Penfield School District

Picture this. There is a large room with rectangular display tables against every wall. About 120 administrators and teachers from small and large districts organize videos, pictures, charts of student, teacher, and administrative formative assessment work on these tables. They are eager to display their learning over a two-year period. The enthusiasm is infectious. As soon as all the work is laid out, individuals walk from table to table eager to review and respond to this work (see Figure 1). What has led to this moment in which administrators and teachers work as a unified learning community to witness and celebrate their individual and collective learning? What has created the tapestry of such a cohesive learning community we call the Monroe Assessment Project (MAP)?

While there is no lack of critics of the value and impact of professional development (Darling-Hammond et al., 2009; Mirage Report, TNTP 2015; Yoon et al, 2007; Bush, 1984), we know that professional development, when done right (Learning Forward Professional Standards), can lead to improved teacher and student outcomes (Darling-Hammond., et. al., 2017). The three-year, multi-district Monroe Assessment Project focuses on the embedded use of formative assessment for both leaders and teachers. It provides compelling evidence that professional development can promote continuous, sustained, and deep learning for everyone.

As the facilitators of MAP, we have discovered at least three essential components to its success. They are:

- working with leaders as learners and strategic planners.

- providing ongoing feedback to leaders and teachers as they design, implement, and revise their work and learning.

- combined regional and in-district differentiated support.

Supporting the learning and work of leaders

A school’s culture is shaped by leaders who support the learning needs of adults as well as children, who know that improvement is a never-ending journey, and who see themselves as learners as well as leaders. A culture of leaders as learners starts with the superintendent.

Such leaders consider their own professional and school-related goals and priorities in a systematic fashion, as they diagnose, monitor, and support teachers’ instructional practices to ensure program cohesiveness and alignment of expectations and work across subjects, grades, and schools. They understand the demands associated with teachers’ work when they develop new curriculum and assessments or adopt and use new teaching strategies, especially when not every teacher in their school system is exposed to such demands. They know how to broker relationships between teachers who are learning and implementing new work and other teachers who have yet to be exposed to such learning, as well as mediate questions that may arise from parents when students are exposed to new practices in some classrooms and not others.

In MAP, while teachers learn how to embed formative assessment practices into their teaching, leaders:

- develop plans for how to position formative assessment within their school improvement efforts.

- examine how to improve upon their uses of formative assessment and feedback with their staff.

- discuss how to develop a shared language and use of formative assessment among students, parents, and staff, and how to broker relationships with teachers with different understandings and practices.

- consider how to integrate assessment-related work with other schools and district initiatives.

Their learning experiences include:

- discussing books and articles on feedback and formative assessment.

- engaging in consultancies in which one leader shares a case study of his or her professional practice, including the analysis of specific structures, processes, activities and/or questions followed by responses and feedback from the group.

- sharing and evaluating their feedback practices and reviewing artifacts that incorporate evidence of these practices.

- planning and implementing learning opportunities for their staff related to the understanding and use of formative assessment.

- engaging in strategic planning work to map and align initiatives.

The differentiated inclusion of leaders and teachers under the same overarching program has the added benefit of increasing everyone’s sense of trust. The message teachers get when leaders are learning along with them is that leaders have their back and are committed to the work. Leaders who receive meaningful professional learning that is related but different from what teachers are learning have an increased sense that their work is worthy, and develop their capacity to support it in their schools. The reflection below illustrates the value of having differentiated learning for leaders.

Having the opportunity to learn alongside teachers, discussing instruction and the feedback the teacher is giving to the student and the types of feedback that would be beneficial for the teacher to receive from an administrator or colleague builds a sense of trust in the authenticity of the feedback received. Additionally, working with teachers as well as differentiated sessions with administrative colleagues deepened my awareness of the importance of aligning the feedback to the individual.

My ability to discuss feedback with teachers and provide individualized, targeted feedback was improved through participation in both learning environments.

-Winton Buddington, Bay Trail Middle School principal, Penfield Central Schools

Ongoing feedback

In MAP, administrators and teachers receive personalized feedback almost immediately after they begin to consider how to implement their learning. This feedback comes from facilitators, peer reviews, and structured self-assessment opportunities. In one year, participants receive feedback at least monthly. The feedback:

- is descriptive, non-judgmental, and descriptive.

- identifies strengths and areas to work on based on a careful analysis of data.

- includes concrete and actionable suggestions for improvement.

- refers to examples from the work observed and models.

- includes suggestions and questions that allow the receiver to maintain ownership and control over their work.

- offers opportunities for dialogue during the revision process.

Making the criteria above transparent to MAP participants and facilitator’s modeling of their use helps to underscore that feedback is about growth and not evaluation. These invitational, non-judgmental feedback opportunities become an established norm and feel very different than the evaluative messages that administrators and teachers receive as part of the professional evaluation process. It enhances participants’ trust in MAP and in its work, as it provides for ongoing dialogue between feedback receiver and giver.

Combined regional and district differentiated support

The ideal structure for transformative and continuous professional learning combines opportunities for work across districts as well as in-district work. Regionally based learning sessions become the learning blocks essential to the learning of all participants. They provide the community with a shared language and key conceptual understandings around the learning, including the design process for and implementation of those practices. The in-district sessions attend to the broader context for the work, individual school/district cultures, as well as the alignment of teachers’ work to school or district-wide goals.

Planning for this combination means meeting the needs of the larger learning community while supporting the learning within each individual district simultaneously. We find that in addition to the common foundational blocks of learning implemented on regionally based days, there is also a need to differentiate those learning opportunities. Two structures that work well include optional school-based mini-learning sessions alongside plenary sessions coupled with opportunities for individual conferences with program participants. Mini-learning sessions are designed from recognized needs among the learning community gathered through the ongoing use of formative data, requests from participants, or analyses of program evaluations and reflections. These structures minimize the amount of time that teachers are out of their classrooms and leaders away from their school.

Differentiating input and learning for administrative leaders and teachers is equally important. Sometimes this involves offering different activities and processing questions for the two constituencies within the same room. Sometimes it means having dedicated learning experiences for administrators and teachers to consider their unique needs and contexts. One MAPper’s experience from the two different role perspectives offers this insight.

I had the unique opportunity of being in the administrative cohort for Cohort 1 and then a designer for Cohort 2. I was able to coach teams while in Cohort 1 and then experience the climb for myself in Cohort 2. The frequency and duration in which we were able to collaborate about our craft were essential. I know it created quite a challenge with substitutes, but I am not sure if we would have grown as much as we did without it. The opportunity to receive feedback on our work and push our thinking father was very powerful. The conferences and breakout sessions were vital to our work.

-Jessica Jones, lead teacher, Fairport Central Schools

Often agendas for the in-district days are co-constructed by the facilitator, district administrators, and teachers. Facilitators keep everyone on the same page and moving in the same direction, but with different structures or materials with which learners engage for supporting the attainment of those goals. For example, in one school, we might provide different mentor text readings and engagement protocols to deepen participants’ understanding of the practical applications specific to their individual classrooms and school buildings. Time spent during the in-district days allows for personalized feedback and “on-the-spot” instruction. This instruction and feedback bring opportunities for leaders and teachers to refine their planning and design work as well as set goals.

Essential, but insufficient

We believe that this work is deeply meaningful and transformative because, as we are wrapping up the third year of this work, administrators and teachers are asking: Where to next? They want the work to grow and continue, and they are looking for structures, systems, processes, and practices to sustain it. We are currently in the process of brainstorming alternatives, wondering how to best expand upon current work to incorporate the interests and needs of leaders and teachers who were not part of the initiative. One of our promising efforts revolves around anchoring a formative assessment continuum (http://www.lciltd.org/resources/formative-assessment-and-feedback-continuum-for-administrators) with samples of formative assessment and feedback for the different levels of quality so that everyone can learn what feedback looks like.

We also know that our emphasis on quality feedback for leaders, teachers, and students is key to the continued learning of individuals. At the same time, we realize that continuous school improvement demands more than individual improvement. School improvement efforts are often compromised by many factors. These include changes in state and federal policies, staff replacements, and shifting resources to support new priorities. We continue to search for more ways of integrating best practices related to professional learning with best practices for school improvement.

Giselle O. Martin-Kniep is president and founder of Learner-Centered Initiatives, Ltd., Garden City, New York. Jeanette Adams-Price is instructional specialist/professional developer at Monroe One BOCES, Rochester, New York.

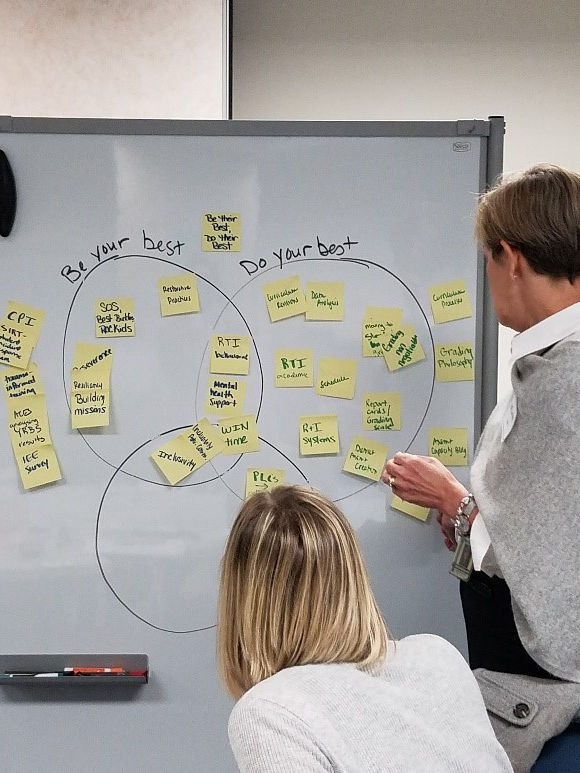

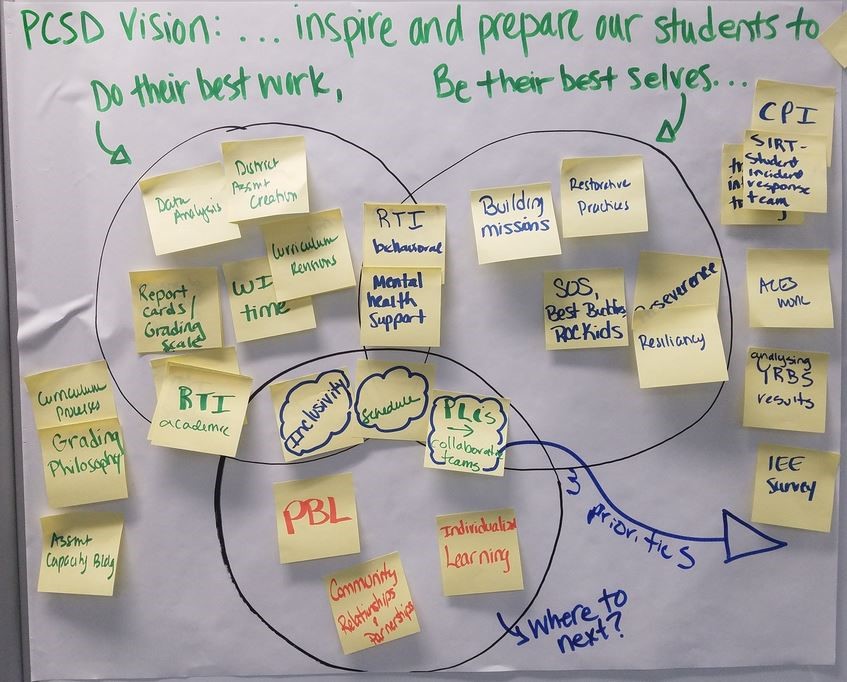

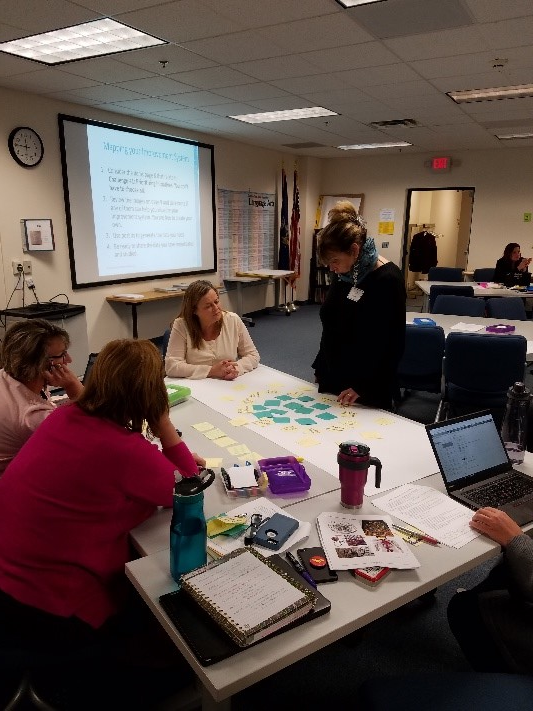

Figure 1: Pictures of Leadership Teams

Pittsford Central School Administrative team mapping out structures, processes, and program connections among district initiatives.

Gates Chili Central School administrative team mapping out structures, processes, and program connections among district initiatives.

Share this content