At 4 years old, Selena Elekovic knew she wanted to “build things.” Her grandfather was a carpenter, so she took wood scraps from his shop to create small chairs “for my Barbies.” “I just liked building stuff,” says Elekovic, who moved from Serbia to a Denver suburb when she was 15. “It just came naturally to me.”

At Cherry Creek High School, Elekovic participated in robotics and the Science Olympiad, where she built a bridge and a robotic arm in competitive events. In the spring of 2017, she jumped at the chance to take part in an internship at Mikron Corporation Denver, a Swiss manufacturer of automation and machining equipment.

“Getting an internship where my main job is to build stuff kind of aligned with my plans,” says Elekovic, who is studying be a mechanical engineer. “When I was told that the internship might lead to long-lasting employment that included money and paid college, I was so in on that.”

Her timing was right. That fall, Mikron partnered with CareerWise Colorado, a program that is working to bring 20,000 apprentices to the state by 2027. Now being watched by other several states interested in adopting the model, CareerWise dubs itself “the first modern youth apprenticeship program in the U.S.”

Selena Elekovic demonstrates a test that potential apprentices take to be accepted into the Mikron Corporation Denver program.

Like other programs, CareerWise targets middle-skills jobs. These jobs, which require more than a high school diploma and less than a bachelor’s degree, now comprise almost 40 percent of U.S. employment. Apprentices who successfully complete the three-year program, starting in their junior or senior year, earn a high school diploma, up to a year of college credit, and at least one recognized industry credential. The latter two come at no cost to the apprentice, who also receives a stipend of about $10,000 a year.

“Students who begin an apprenticeship find themselves in a professional, high-expectation environment where they are pushed to develop and grow rigorously. This is not going to be for every single kid,” says Meaghan Sullivan, CareerWise’s chief program officer. “But for the kids who are going through the motions, this can speak to them in ways that school never does.

'It All Makes Sense'

While other internships and apprenticeships continue to be used across the state, CareerWise, which was founded in 2015 by Intertech Plastics CEO Noel Ginsburg, is modeled on Switzerland’s apprenticeship program. Formally launched in the summer of 2017, it is built around five career pathways: information technology, financial services, advanced manufacturing, business operations, and health care.

Today, CareerWise is in 14 Colorado districts, as well as in independent and charter schools. About 450 students —more than half from the Denver area—are participating in the program. The growth seems small, but that is partly intentional, Sullivan says, as CareerWise works out the kinks in implementation and figures out the best ways to engage employers, schools, students, and parents.

“If there’s not employer ROI (return on investment), this can’t go to scale,” she says. “Employers will engage in philanthropic support to a point, but only as long as it’s productive and real. Our goal is to find partnerships in which students integrate completely into your operation, so that when you invest in all of that training you get the benefit because the students have the expertise.”

Modesto Quezada, a mechanical technician deputy for Mikron, watches as apprentice Selena Elekovic works on the assembly test. Quezada helps oversee the work of apprentices at Mikron.

Ursula Renold, director of the Comparative Education System Research Division at the Swiss Economic Institute in Zurich, is one of the foremost international researchers on apprenticeship programs. She calls the CareerWise effort “radical innovation” and says education and business leaders must be patient as the program is built out.

“Changing social and educational institutions takes time,” Renold says. “This is not an overnight process but one that will take 10 to 20 years. As educators, you are half of the rubber that meets the road. Business is the other half. You will have to identify these folks, survey them, and find out their willingness to train your students. But they have to meet you halfway.”

The Mikron facility, located in Englewood, now employs seven apprentices and five interns from the Cherry Creek School District, says Ed Baldwin, the district’s human resources director. Students interested in mechatronics are identified by the district’s STEM teachers. They are interviewed for the positions, as are their parents. Before they are selected, students also take mechanical assembly tests to show their aptitude.

“There has been a perception that folks who participate in the skilled trades were not smart enough to go the traditional college route,” Baldwin says. “That is something we have to rebrand to this generation of high school kids as a really viable career path and an honorable one, one they can be proud of.”

Quezada and Elekovic.

Asked what she’s learned at Mikron, Elekovic lists: working with a mill lathe, how to make and “tap” holes, and how to “assemble things properly.”

“I’ve learned about different glues. I’ve learned about how plumbing works. I’ve learned quite a bit about pneumatics,” says Elekovic, who graduated from high school in 2018. “It’s neat because it’s helped me to make connections with the college classes I’m taking now, like quality process and quality management. I knew what they were talking about, in a real way, because of what I’ve already learned here. It all makes sense.”

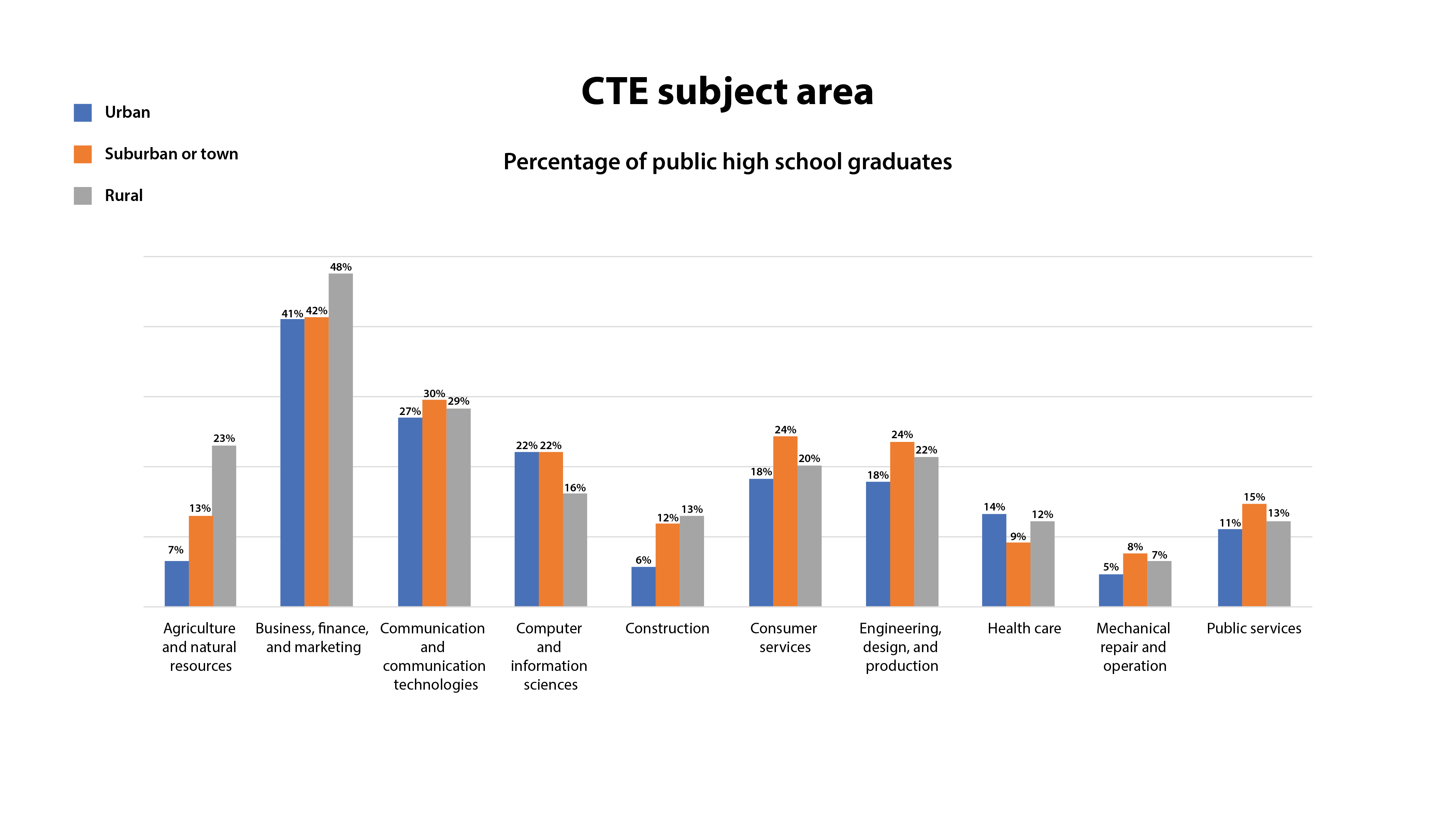

Students in different geographic areas and CTE credits

Simple Yet Difficult

As career and technical education programs make a comeback, researchers are looking for ways to avoid the pitfalls that plagued vocational education in the past. MDRC, a nonprofit organization started by the Ford Foundation, issued a policy brief in late July that noted programs such as CareerWise are facing many of the same challenges. Among them: how to make sure information is available to students and families; determining what the eligibility and screening criteria are for selecting apprentices and interns; developing effective employer partner programs; and dealing with issues such as transportation and equitable funding for the programs.

“It’s the little things that seem simple yet are difficult to solve,” Sullivan says. “The simple reality of how we get kids to work. The transportation challenge exists in rural areas as much as it does in urban communities. Finding the right company and the right job in a location that you can get to in a reasonable time is a trifecta that can be very challenging.”

Mike Wadleigh, an internship and apprenticeship specialist for Cherry Creek Schools, says the district has set up 90-minute seminars for students to work on job readiness skills. The district, which is opening an innovation campus this fall, has 42 students participating in CareerWise. Cherry Creek also is experimenting with a future educator pathway, in which students interested in becoming teachers work as paraprofessionals in schools.

“With every new program or new venture there are going to be some definite stumbling blocks, but for the most part this has been very successful,” Wadleigh says. “Our students are having amazing experiences and they’re learning a lot more out in their apprenticeships than they would learn in the classroom. We see how much more mature they are, how they handle themselves, how their academics change. And it’s all because they see a value in life after high school.”

Max Paulson, a senior at the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, is an apprentice in the Denver Public Schools information technology department.

Denver Public Schools, the state’s largest district, also has the largest CareerWise program with more than 70 apprentices. But while district officials point to the same positives as Wadleigh and Sullivan, they also acknowledge the challenges of developing a program that serves all students on an equal playing field.

Anthony de la Rosa, Denver’s senior manager of innovation programs/CareerConnect, says more students are interested in apprenticeships than are available through local businesses. A number of students now work as apprentices for the city and the school district, two of Denver’s largest employers, but de la Rosa wants to expand into the private sector.

“We need to make sure when it comes to equity and inclusiveness that it’s not just a talking point for businesses, but something that is of actual value,” he says. “Many of our students are not just dealing with work and school. They are dealing with stuff at home, and the wages they are earning go straight into the family so they can put food on the table. We have a chance to change the trajectory of their lives with this program, but we also must make sure the student feels supported, safe, and valued in that space. It is a challenge.”

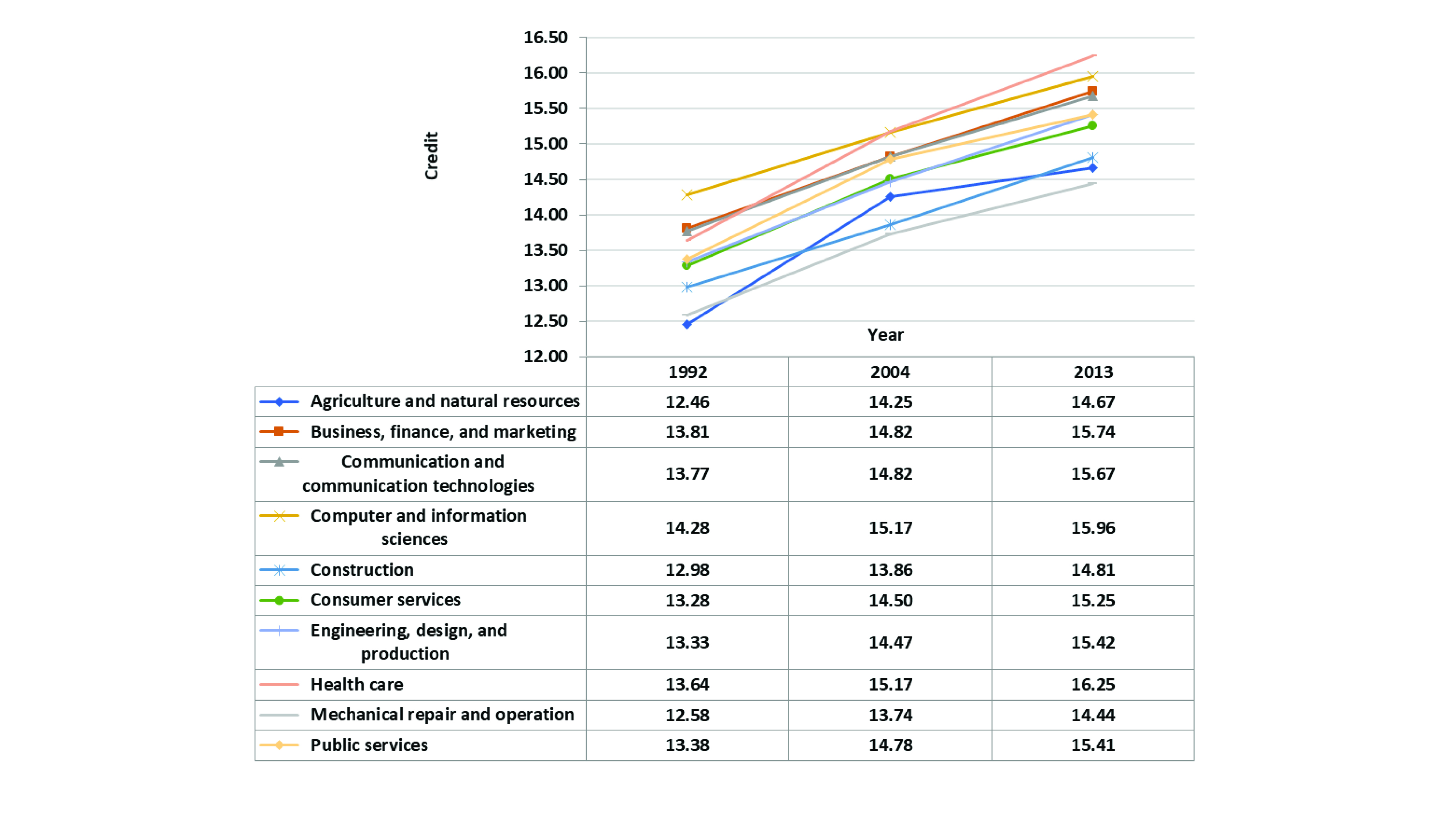

Academic Credits CTE Students Earn

A Head Start

Max Paulson, Fin Blackett, and Emiliano Linares Gonzales are apprentices in the Denver Public Schools’ information technology department. Paulson and Blackett are seniors at the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, while Gonzales is at the West Leadership Academy.

Sitting in a breakroom in the downtown office, the three talk about the challenges of their commute. While Blackett lives only 15 minutes away, Paulson’s commute takes 45 minutes to an hour. Gonzales rides the bus an hour to 90 minutes each way.

Now in their second year with the program, each is quick to note the advantages of the apprenticeship: real-world experience in a high-stakes professional environment and improving soft skills such as communicating with clients and customers. All plan to go to college, and each believes the apprenticeship will give them a head start on their future careers.

“To do this, you’re trading off your freshman year of college, and also trading your junior and senior year of high school,” says Paulson, who is working in enterprise application development. “I keep hearing that college is not as good as it used to be, especially in the tech field where it’s more about what you know than what piece of paper you have. The paper gets you in the door, but once you’re in there what you have is limitless. And I’m already a step up because of this.”

Emiliano Linares Gonzales is a senior at Denver's West Leadership Academy and an apprentice in the Denver Public Schools information technology department.

Blackett, who is working in the district’s data center and is focusing on information security, says he has learned to appreciate the difference between “reading how to do something and then actually doing it.”

“You can see something that is done perfectly in documentation, but you learn that everything can change when it is applied in real life,” Blackett says. “A lot of people can code and set up network hardware but not know how to implement it when something goes wrong. If you’re only getting information out of a book, you won’t know what the pitfalls and shortcomings are.”

Gonzales, who works in field services administration, says he has found great value in “learning how to interact with customers in all types of different situations. The people you work with are much older than you, and it’s good to know that you can interact and apply your skills to help them do their jobs better.”

All three say they don’t miss the regular day-to-day routines of high school. If anything, they wish their classmates understood the value of an apprenticeship.

“The whole thing is an extra year, a 13th year, and I understand that a lot of people don’t want to miss out on their freshman year of college,” Paulson says. “But adults tell me they wish they had what I’ve got, and I say I wish my friends understood how important this is to them and their future. That’s where the narrative shift needs to happen, because this is an extremely valuable thing. It can be the equivalent to two or three years of a head start on your life.”

Fin Blackett, like Paulson, is a senior at the Denver School of Information and Sustainable Design and an apprentice with the Denver Public Schools information technology department.

Twenty miles away, in Englewood, Elekovic is entering her final year as an apprentice. In May, she will receive a certificate in engineering manufacturing from Metropolitan State University. She then plans to pursue a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering while continuing to work at Mikron.

“They’ve been very supportive, and they know my plan is to get more schooling even when I finish the certificate,” she says. “The way I look at it, I’m on track to get a high-paying job in two-and-half to three years. When I’m done, I’ll have the experience they’re looking for. I hopefully will get my bachelor’s degree at 23 and will already have four years of experience and certificates thanks to this program.”

Because of the work-based training she has received, Elekovic finds herself showing recent hires with college degrees how to do certain tasks. “It’s because I’ve already been here, doing the work,” she says. “Everybody has their own path. Mine is a little different, but it has worked out for me.”

Share this content