This past year I conducted student, parent, and staff focus groups for a Midwestern school district as a part of their strategic planning process, which they were conducting from a racial equity perspective. As always happens when our students know their voices are being heard, they were brutally honest about their school experiences.

When asked the question, “What barriers are you encountering in getting a good education here?” they rattled off a list similar to one that I’ve heard students say in every part of this country:

- They do not believe they are listened to or respected.

- They want/need an adult they trust to talk to.

- Racial, gender, and sexual identity slurs are frequent and not addressed by the adults in the system. (Ability/disability slurs also were mentioned, but at a much lower frequency.)

- They experience access, opportunity, and participation discrimination in athletics and activities.

- Bullying, harassment, and intimidation are problems across grade levels and buildings.

- Discipline is inconsistently applied to students based on their gender and/or race.

As one student eloquently stated, “There’s a lot of barriers, and sometimes you don’t even know what or where they are.”

Security First

Were any of the barriers they raised related to academics? No. While academic-related comments showed up later in these conversations, their first responses were linked to how they felt, and what they were experiencing in the school environment. These comments are no surprise to anyone familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs or the principles of social and emotional learning. Until a person’s basic needs are met, and he or she feels safe, secure, loved, and included, both in the school setting and in their other environments, it is extremely difficult to focus on learning.

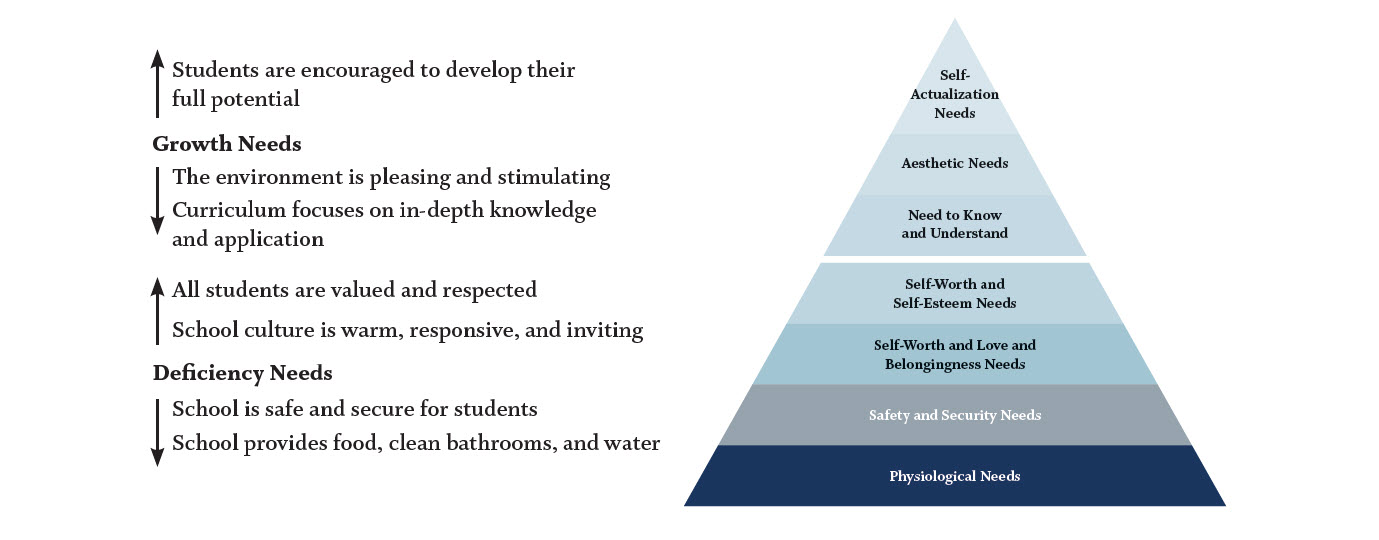

Maslow’s pyramid and the CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning) wheel of social-emotional needs are helpful tools for understanding the dynamic students need to feel safe, included, and supported so they can thrive and experience success in school.

Maslow’s Hierarchy

- Physiological needs

- Safety and security

- Love and belonging

- Self- esteem

- Self-actualization

Social-Emotional Learning Principles

- Self-awareness (understand and manage emotions)

- Self-management (set and achieve positive goals)

- Social awareness (feel and show empathy to others)

- Relationship skills (establish and maintain positive relationships)

- Responsible decision-making

When focusing specifically on school environments, the pyramid shows what Maslow’s hierarchy looks like in the school security context.

As this visual makes clear, social and emotional skills are embedded in the different levels of the pyramid. For growth and learning to occur, the bottom tiers need to be in place for students. There is an abundance of research supporting the fact that a positive school and classroom climate results in:

- Improved attitudes and behaviors;

- Reduction in classroom and criminal misconduct, substance abuse, pregnancy, dropout rates, and mental health issues;

- Better relationships with peers, families, and adults;

- More time spent on teaching and learning, and less time spent on classroom management;

- Increased academic performance, graduation rates, postsecondary enrollment and completion, employment rates, and average wages.

Fear and Hurt

Let’s return to the student focus groups and their conversation about school safety issues. The days I spent conducting these focus groups were less than two weeks after the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, school shooting. Every middle and high school student group brought this up. And every one of them could tell me where, and at what time, a shooting like that would take place in their buildings. They were disturbed, hurt, and angry that few teachers had provided the time or space for them to talk about how they were feeling about this tragedy.

Moreover, multiple students mentioned that this same dynamic had happened after the 2016 presidential elections, and they were still resentful that their fear, hurt, and vulnerability had not been “seen” and acknowledged by the majority of their teachers and counselors. I found myself wondering, “How much learning has taken place in these buildings since the Parkland school shooting, when these students’ basic needs to feel safe, seen, and supported have clearly not been met?”

Different Perspectives

When the subject of school safety was specifically discussed in the focus groups, a consistent pattern emerged: Students of color and white students had totally different perspectives on police presence in schools and what that meant for their personal safety. Seeing police on their campus made the white students feel safe — and they stated they would like more security officers.

Seeing police on their campus did not make students of color feel safe. They cited experiences of seeing the public handcuffing of students inside elementary and secondary schools. They talked about how nervous they felt walking past armed police officers monitoring vehicle traffic flow around their buildings.

Ways to Respond

There are many issues surrounding school safety, and it will require the board to initiate some hard conversations. As these student focus groups revealed, there are several system issues both in their schools (i.e., multiple types of discrimination) and in the community (i.e., distrust of law enforcement), that are impacting their sense of physical, social, and emotional safety and well-being — which is affecting their ability to thrive in the school environment.

In today’s climate of increased concern about student safety and well-being on our campuses, there are several ways school boards and district leadership teams can respond:

Develop a solid understanding of the elements of a positive school climate and ask how social-emotional learning principles are being implemented in your buildings to improve it.

Get feedback from your students about what their safety needs are. A board study or work session with students will provide you with invaluable information about what students are experiencing.

Visit the NSBA Center for Safe Schools to learn more about this topic and what resources are available to assist you.

Prioritize policy and resource allocation decisions that center students’ needs for a safe, supportive, and inclusive environment; and staff needs for professional development in social-emotional learning principles and how to create positive classroom/school climates.

Take the lead in bringing together other leaders in the education, health/human services, youth development, and law enforcement sectors to collaborate on how to improve the physical, social, and emotional safety of your community’s children. The Georgia School Boards Association hosted an outstanding Safety and Social-Emotional Learning Summit in March 2019 which brought together representatives from these different sectors to start this conversation, network, and learn together.

Mary E. Fertakis (mfertakis@comcast.net), an NSBA equity consultant, is a former school board member in Tukwila, Washington.

Share this content