Sixty-nine years ago, black residents from a small South Carolina town filed a lawsuit that ultimately would change history. Four years and one day later, on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court made sure of that.

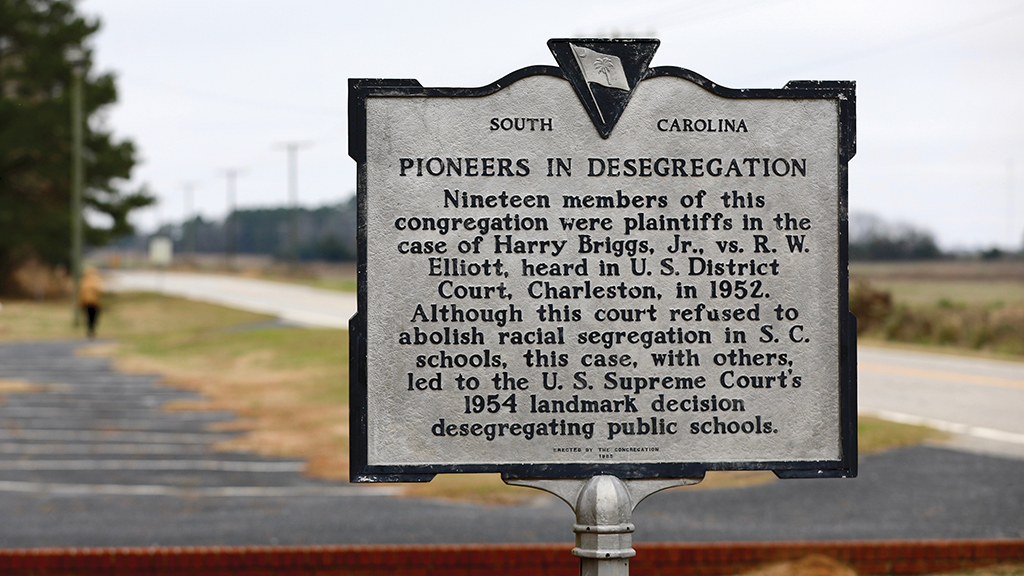

The court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education led to the eventual desegregation of our nation’s public schools and helped spark the civil rights movement. The roots of Brown, however, started with Briggs v. Elliott in Summerton, South Carolina, a fact that remains largely forgotten except among education historians, lawyers, and scholars.

As the 65th anniversary of the Brown decision approaches, Summerton’s almost silent resistance, if not outright indifference, to its place in history comes as no surprise to many of the community’s African Americans, even as businesses leave, the public schools struggle, and the population continues a slow but steady decline.

“Things won’t change until attitudes and minds change, and that’s not happening,” says Bea Rivers, who was 13 when her parents became the second family to sign the Briggs petition in 1950. “I’ll bet you there are still people in this town who believe there was not a Briggs v. Elliott. They don’t know, or won’t acknowledge, that it existed.”

Fifteen years after interviewing Rivers for an ASBJ story that marked Brown’s 50th anniversary, I returned to Summerton for another look at its recent and distant past. While its future is unknown, its past remains instructive as integration in America’s public schools has declined to the lowest levels in 40 years and as rural districts struggle to be funded at levels closer to those of their urban and suburban peers.

What I found was a town that time forgot.

Rural School Woes

Summerton is in South Carolina’s rural “Black Belt,” a stretch of farm land with little industry and high poverty, in the southwest part of Clarendon County. It is part of the “Corridor of Shame,” a title given to the state’s rural schools in a 2005 documentary about a long-standing legal battle over what constitutes a “minimally appropriate education.” Clarendon District No. 1, where 97 percent of students qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, was one of 30 plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

A judge ruled for the districts in 2005, but a years-long appeals process ended with the state Supreme Court returning school funding oversight to the legislature in 2017. Meanwhile, frustrated teachers across the state have threatened to walk out over low pay and lax benefits, mirroring similar efforts around the country.

“The legislature’s lack of support across this state is just shameful,” says the Rev. Robert China, pastor of Liberty Hill AME, the church attended by most of the Briggs v. Elliott plaintiffs. “The larger cities — Greenville, Columbia, Lexington — have large tax bases. The legislature puts the same criteria and expectations on schools here. That’s like you having an 18-wheeler to move a load and you give me a Ford F-150 pick up and tell me to do the exact same thing. There’s just no equity. There’s no sense in that.”

Complicating matters further, especially in a struggling town with no industry, was the 1,000-year flood that hit Summerton and other parts of the state in October 2015. The Meadowland Apartments, where many of Clarendon No. 1’s students live, was seriously damaged and has just now been rebuilt. Several dwellings in the poorest section of town have been abandoned or still are not repaired. Two hotels near I-95, which cuts through Summerton, closed and have not reopened, as have several small businesses.

“That flood was just devastating to people. They were just homeless,” says Kathleen Gibson, director of the district’s Community Resource Center. “Even though I don’t live in those apartments, my heart is there because our kids are there.”

Superintendent Barbara Champagne attributes much of the district’s steep enrollment decline to the flood. While the district’s racial makeup remains the same as it did in 2003-04—96 percent of students are black—enrollment during the same period has dropped from 1,288 to just 777.

“So many people left, and they didn’t come back,” Champagne says, noting the enrollment drop places a further financial burden on a district already struggling to make ends meet.

What Led to Briggs

I was in a rental car with Illinois plates the first time I drove through Summerton in the fall of 2003. I had worked for ASBJ for two years at the time, and then Editor-in-Chief Sally Zakariya tasked me with developing stories on the 50th anniversary of the Brown decision.

Cecile Holmes, a 30-year friend and colleague who is a journalism professor at the University of South Carolina, and I started examining Briggs v. Elliott. We sketched out a plan that would involve taking her students to Summerton — about 65 miles from the campus in Columbia—to understand the town, its culture and churches, and its schools.

What led to Briggs v. Elliott started in 1947, when petitioners led by the Rev. Joseph A. DeLaine sought a bus from the Clarendon No. 1 school board so black children would not have to walk as many as nine miles each way to school. A lawsuit filed by farmer Levi Pearson was dismissed, but service station attendant Harry Briggs and his wife, Eliza, sued the school district in 1950 to challenge the “separate but equal” status of blacks. They were represented by Thurgood Marshall, a lawyer with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund who later became the first African-American justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Briggs lawsuit, along with others filed in Delaware, Kansas, Virginia, and the District of Columbia, was consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education. While the cases raised different issues, the primary legal argument was that separate school districts were “inherently unequal” and violated the 14th Amendment’s “equal protection clause.”

Marshall personally argued the case in front of the Court, using much of the evidence gathered during his trips to Summerton from 1950 to 1952. Among them: social scientist Kenneth Clark’s infamous “doll test,” which helped show segregated schools made black children feel inferior to their white peers.

Working with Holmes and her students, I conducted extensive interviews with DeLaine’s three children, as well as with Rivers and others whose parents were on the original lawsuit. After high school, Rivers left Summerton but moved back in 1995 to care for her ailing mother. With the DeLaine siblings, she was part of a group of alumni that took over the Briggs-DeLaine-Pearson (BDP) Foundation, a nonprofit seeking to draw attention to Summerton’s place in history and raise money for a youth community center.

Before our first set of interviews in 2003, I wanted to get a feel for the town. As I drove down U.S. 301 and then onto Main Street, a police car pulled in behind me. I was heading toward the former Scott’s Branch High School, where there’s a small marker honoring the original plaintiffs, and had moved into the “other side of town.”

The patrol car’s lights flickered, and I pulled over. The officer, who was white, checked my driver’s license and asked what I was doing. I explained and then was allowed to leave, but the random check unnerved me. The officer looked me in the eye and told me to “be careful.”

I wasn’t sure what he meant.

Unchanging Attitudes

Fifteen years later, Joseph DeLaine Jr. brings up that encounter with the officer when we talk about how things are — or aren’t — different in Summerton. Now 85, DeLaine still is the torch bearer for his father and Briggs v. Elliott’s place in history.

DeLaine, the oldest child and his father’s namesake, was in high school when the original lawsuit was filed. He vividly remembers when his father’s church was burned to the ground a few months after the Brown decision. Ten days later, after gunshots were fired into his home, DeLaine Sr. fled Summerton under a blanket in the back seat of a car. He died in 1974 without returning to South Carolina.

“When I talk to my nieces and nephews, most of whom are in their mid 50s now, they don’t understand this, and they can’t comprehend it,” says DeLaine, who lives in Charlotte.

DeLaine, a representative on the federal Brown v. Board Commission formed for the 50th anniversary, was on hand when his father, Harry Briggs, and Levi Pearson were posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 2004. Despite those honors at the federal level, he remains frustrated that local and state politics and attitudes about the case have not changed.

“There’s a little more awareness, but not that much,” DeLaine says. “When we talk with people born and raised in South Carolina, they know all the alleged details about Brown v. Board but are not aware of Briggs v. Elliott. Even in Clarendon County, you can talk to people down there who don’t even know what Briggs v. Elliott meant.”

For much of the past two decades, since retiring from his job in New Jersey and returning to the Carolinas, DeLaine has struggled to reconcile feelings about his hometown with the need to do something for Summerton’s children.

“My father had a deep investment as the leader of this whole thing, and I would like to see some benefit that the community enjoys out of all of this,” DeLaine says. “They’ve gotten none thus far.”

Even though he says he’s mellowed — “Age does have its toll” — he remains prickly when asked about progress on the BDP Foundation’s community center, which remains half-finished due to “red tape” and slow fundraising.

“At this point, we’re not dead with the building, but we are in a hiatus,” he says. “We’ve gone through a lot of baloney, expenses involved with each of the delays and requests for information that is nonexistent. The money adds up, and it means we have less capital to put into the center. It’s a frustrating circle.”

District Struggles

On a cloudy, cold mid-January morning, Champagne, China, Rivers, and Gibson are in the small boardroom at the Clarendon School District No. 1 office. The room, which seats 20 to 30 people, has a framed poster commemorating Briggs v. Elliott, a poster of Thurgood Marshall, and T-shirts marking the lawsuit in scrapbook boxes.

The four welcome the opportunity to shine a light on the district’s struggles, but frustration around the table is evident. Even though the district’s graduation rate has improved, test scores in the lower grades remain poor. The teaching staff, one-fourth of whom is international, is in a constant state of turnover.

“We have no tax base in this town. There’s no jobs. People raising families can’t live here. Why would you not give rural school districts more money?” Rivers asks. “Mrs. Champagne can hire the best teachers, but in one year another district is going to offer them more money and they’re gone.”

Much of the conversation revolves around Summerton’s inability to fully integrate. Words like “embedded” and “systemic” are used to describe the town’s entrenched malaise.

Consolidating the county’s three public school districts has been discussed in multiple venues, but no agreements have been reached. Clarendon District No. 2, the highest funded and highest achieving — of the systems, has rejected proposals to merge food service, maintenance, and transportation. Eventually, Champagne predicts, that could lead to forced consolidation by the state.

“It’s really the attitude. How do you change the attitude?” Champagne says. “As an educator, it goes back to making the school system better, but the other community really wants things to remain the same.”

In terms of education, the “other community” is represented by Clarendon Hall, a private Christian school founded in 1965 as a way to help whites avoid forced integration. (Calls to the school to discuss Briggs and Brown, both in 2003 and for this story, were not returned.)

If you go into white businesses in town, such as the Summerton Diner, you see fundraising materials and donation jars for various Clarendon Hall activities. No such materials are to be found promoting Clarendon No. 1.

Gibson, a Summerton native, was born the year before the Brown decision. Her father, Henry Lawson, was part of the Briggs v. Elliot case and later owned a gas station in town. He also chaired the Clarendon No. 1 school board and served on the city council, but said in 2003 that he and other black members “never felt accepted” as equals.

On-the-record statements like that, especially from city and school officials, are rare. No one wants to talk badly about their neighbors, especially to an outsider who is taking notes.

Or, as one Clarendon District No. 1 official says, “You don’t live here every day. I do.”

The Stand

Joe Elliott, the grandson of the school board chairman named in the original lawsuit, knows the repercussions of stating his opinions. His family lived in Summerton for six generations.

“My immediate family did not use the ‘n’ word,” says Elliott, who was 9 when Briggs was filed. “We were just like ostriches with our heads in the ground. If my family talked about race, they talked about it in whispers. No one really mentioned the case. My grandfather used expletives for the Rev. DeLaine, but we weren’t really aware of what was going on when we were younger.”

After a career as a teacher and administrator, including at an all-black private school, Elliott returned to Summerton in 1999. As Clarendon Hall’s headmaster, he took steps to integrate the school and set up games against Scott’s Branch High, which serves Clarendon District No. 1 students. “You would think the earth had turned upside down,” he says.

When we first met in 2003, Elliott had retired to care for his ailing wife and was living in a house that his mother’s family had owned for more than 200 years. At the time, he was coming under fire for publicly stating his desire to honor the Briggs plaintiffs.

“I realized they were the spark that started the whole civil rights movement, and I thought they should be regarded as such,” Elliott says. “That’s when things got a little hectic for me in Summerton, the stand I took. People became more distant. I went from being Joe to Mr. Elliott. People I thought were my friends wouldn’t come over to the house anymore. I didn’t feel nearly as much at home.”

In May 2004, weeks after my initial story appeared in ASBJ, Elliott appeared on a panel focusing on Briggs v. Elliott and the 50th anniversary. That night, while he sat in his living room, his home was vandalized.

“I had a glass front door, and it sounded like a baseball bat hit it. I think it was children who probably heard their parents talking that were the culprits. But that was just the last straw,” he says. “My wife was very sick. A lot of things were weighing heavily on me. It was just time to leave.”

Elliott moved to Aiken about 90 miles away. His family home is now vacant.

Honoring the Past

Fifteen years ago, as I finished reporting my initial story, I mentioned Elliott’s predicament to Joe DeLaine Jr. while standing outside his Charlotte home. DeLaine said he would make it a point to reach out to Elliott.

It was a small sign of hope, and DeLaine kept his word. Today, the two are working together on a project to cement Briggs v. Elliott’s legacy: raising money for a statue in honor of Joseph A. DeLaine Sr. and a plaque honoring the plaintiffs.

“The plaintiffs in that case were just uncommonly brave,” says Elliott, who has appeared with DeLaine on several panels over the past 15 years. “No one was braver than the Rev. DeLaine. No war hero. No one. He put his wife, sons, and daughter at risk to do this. When your family is at risk and imperiled, that takes extraordinary courage, and it should be recognized.”

The statue is the brainchild of Carl Elliott, Joe’s second cousin and a professor at the University of Minnesota, who had the idea for the statue after a 2017 white supremacist protest turned violent in Charlottesville, Virginia. “I thought, by virtue of our family history, maybe we’re in a position to do something that other people can’t,” says Elliott.

Carl Elliott got 20 members of his family to sign a petition that was sent to the South Carolina legislature asking for the statue to be placed on the state Capital grounds. “We never got a response from anyone in the legislature, but there was something good that came from it,” he says.

Luther Ragin, the grandson of Briggs plaintiffs, is the founding CEO of the Global Impact Investing Network in New York City. When he saw Carl Elliott’s op-ed in the New York Times about the statue, Ragin offered a $100,000 donation. That’s about half of what is needed, and the Central Carolina Communities Foundation is raising the rest.

For DeLaine, the statue and plaque would be the acknowledgement his father has deserved for almost 70 years. It also would send a signal to Summerton that the cause sometimes is bigger than anyone is willing to recognize.

“You would not believe the enmity I once had,” DeLaine says. “I would literally stop on the highway to spit on South Carolina’s ground before I left. That’s how much I hated the place. But, after my father died and my mother passed away, I realized I wanted to help. That’s what my father did, and I needed to do something to honor him, even if I will never go back there to live.

“I don’t waste my time with hate at this point. Anger doesn’t help me anymore.”

Share this content